Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky, the Russian composer famous for his ballets, symphonies, and the 1812 Overture, completed his final ballet, The Nutcracker, while dealing with a series of personal crises. Amid death, financial insecurity, and unrequited love, he overcame writer’s block to create one of classical music’s most enduring holiday traditions. Within the ballet’s superficial tale of a young girl’s magical journey, the composer saw “not only the child’s soul with its special view of its surroundings, but … a moment of qualitative change and transformation in a person on the threshold of youth.”

View author's page

Reading time estimated : 13 min

The birth of The Nutcracker

Tchaikovsky and his collaborators

Following the successful premiere of Sleeping Beauty, Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky received a commission to compose a new ballet based on a decades-old tale of a living nutcracker. In 1816, German polymath E. T. A. Hoffmann published “The Nutcracker and the Mouse King,” a magical tale of a young girl, Marie (renamed Clara in the ballet), whose favorite toy comes to life. After defeating the evil Mouse King in battle, he transforms into a human prince and takes Clara to rule as his queen in a kingdom of living dolls.

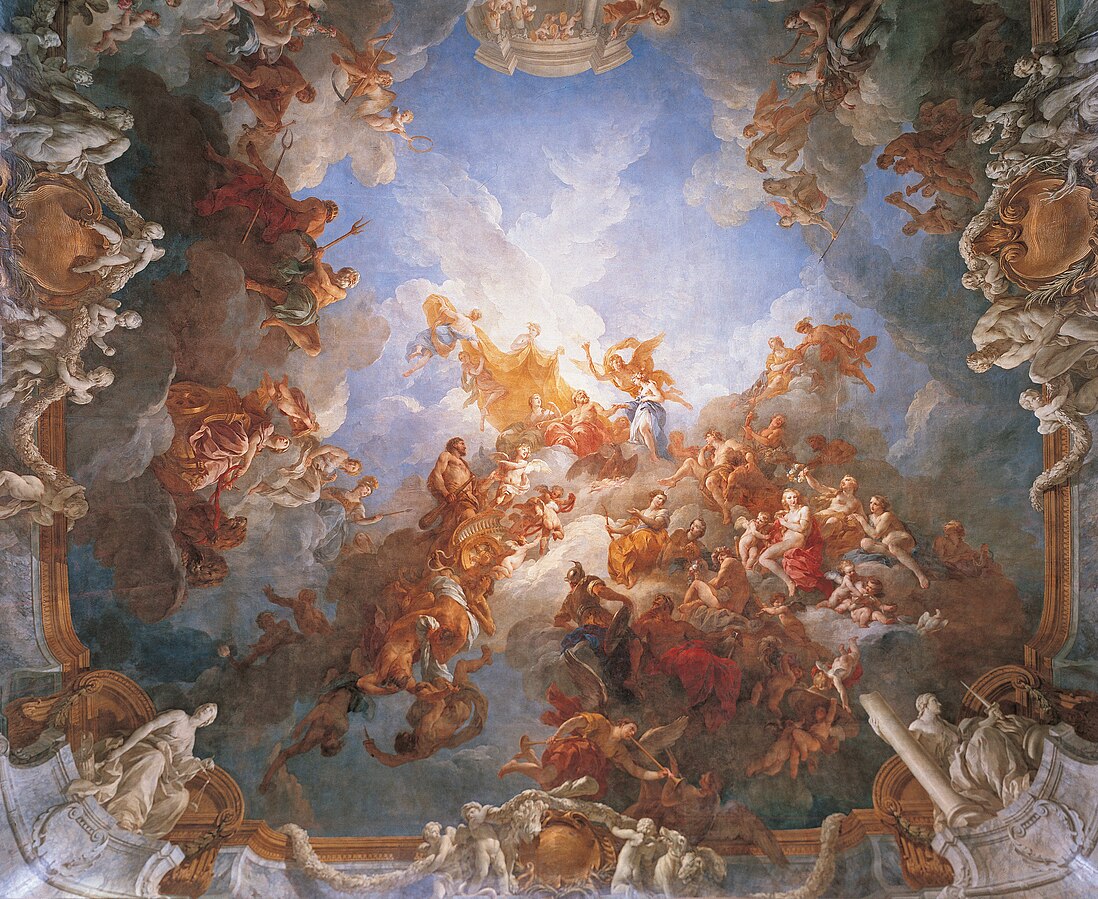

Fantastic scene

Marius Petipa, who had choreographed Sleeping Beauty, adapted the story and oversaw choreography. Petipa provided detailed instructions for each number, including tempos and the number of bars for each scene. When Petipa fell ill his assistant, Lev Ivanov, stepped in to complete the choreography.

Tchaikovsky: Fear, Loss, and Desire

Tchaikovsky’s life was plagued by loneliness and loss. The deaths of friends and family, as well as the loss of his most important patron, weighed heavily on him in his final years. Perhaps worst of all, the conservative mores of tsarist Russia forced Tchaikovsky to remain closeted. Robbed of his desire for romantic partnership, the composer channeled his frustrated energies into his work.

Early love and loss

Two decades before The Nutcracker, Tchaikovsky had a relationship with Eduard Zak, a teenager fourteen years his junior. He was devastated when Zak, at the age of nineteen, took his own life. Tchaikovsky later entered into a short-lived, disastrous “lavender marriage” with a woman. While the nature of his relationship with Zak remains uncertain, it had a clear impact on the composer: the love theme from his Romeo and Juliet Overture was likely inspired by the boy. Some fourteen years after Zak’s death, he wrote in his diary, “Before going to sleep, thought much and long of Eduard. Wept much. Can it be that he is truly no more??? … It seems to me that I have never loved anyone so strongly as him.”

Tchaikovsky also fell in love with the violinist Iosef Kotek, one of his students at the Moscow Conservatory. Whether his feelings were reciprocated is unknown, though some assert that the pair were lovers. Kotek assisted in the composition of the Violin Concerto in D Major. The composer wanted to dedicate the work to his pupil but worried that doing so would spread gossip about his sexual orientation.

Nadezhda von Meck

Tchaikovsky relied on the patronage of eccentric businesswoman Nadezhda von Meck for many years. This allowed him to become Russia’s first full-time composer, but the stipend came with an unusual stipulation: she insisted that they never meet. Nevertheless, the pair kept an extensive correspondence, and the composer came to regard her as one of his closest friends. He was devastated when she suddenly ended their relationship. Her final allowance ran out around the time Tchaikovsky began work on The Nutcracker.

“Bob”

After losing von Meck’s patronage, Tchaikovsky turned to his nephew, Vladimir Davydov, as a confidant. The composer was deeply infatuated with Vladimir, whom the family nicknamed “Bob.” “With all my soul I long to join you, and think about it all the time,” reads one letter to his nephew, and to his brother Modest he gushed, “truly I do adore him, and the longer it lasts, the more powerful it becomes.” He dedicated his final major work, the Symphony No. 6 in B Minor, to Bob, and bequeathed to him the bulk of his copyrights and royalties.

Fear of getting older

Tchaikovsky’s letters reveal his deep discomfort with aging. In a letter to Modest, he wrote of his desire for Kotek, “… passion rages within me with such unimaginable strength … Yet I am far from the desire for a physical bond. … It would be unpleasant for me if this marvellous youth debased himself to copulation with an aging and fat-bellied man.” He reflected similar sentiments in letters to Bob. Shortly after completing sketches for The Nutcracker, he complained, “the old man is definitely deteriorating. Not only is his hair thinning and as white as snow; not only are his teeth falling out and refusing to chew; not only is his sight deteriorating and his eyes getting tired ….” The following month, he advised his nephew, “Enjoy your youth and learn to cherish time.” For a man bemoaning the loss of his youth, escaping into Clara’s timeless fantasy may have been welcome respite.

Writer’s block

Tchaikovsky’s letters reveal his struggle to complete the ballet. The death of his younger sister Alexandra was a devastating loss, and he found himself uninspired and daunted by the ballet itself. “A burning melancholy constantly gnaws at my heart,” he despaired. He particularly struggled to complete the Confiturembourg music, so much so that he asked to postpone the project. He found Petipa’s libretto dramatically unsatisfying, particularly the near-total separation between the pantomime of Act 1 and the fairy-tale world of Act 2.

Deeper Meaning in The Nutcracker

Key signatures and symmetry

“Tchaikovsky saw in Petipa’s plan not a fantastic féerie … but a serious work, profound in content. In it is revealed not only the child’s soul with its special view of its surroundings, but … a moment of qualitative change and transformation in a person on the threshold of youth…. This psychological hidden meaning became the basic content of the music.” — musicologist Yulia Rozanova

Tchaikovsky realized that on its own, the structure of the ballet was incomplete. The first half seemed an unnecessary prelude to the divertissement of the second. His solution was to use key signatures and dance forms to create symmetry between the two acts. The overture begins in the key of B-flat major, and by the end of Act 1 the key has shifted to the remote key of E major. This tonal distance suggests the separation between the humdrum Silberhaus home and Confiturembourg. By the end of the ballet, the key has returned to B-flat. The key of C major also plays a significant role. This tonality envelops the conclusion of the Christmas party, as well as the Nutcracker’s transformation and the appearance of the Christmas woods. Lacking sharps and flats, C major has long held associations of purity and childlike innocence.

Tchaikovsky scholar John Wiley notes further symmetry in the dances. “He makes the second dance of Drosselmayer’s dolls a trepak, thus creating a symmetry with the trepak of the divertissement. Clara’s dance holding the nutcracker in her arms in Act 1 is balanced by the Dance of the Mirlitons—both are polkas in D major; and the large ensemble waltzes in each act form spectacular parallels to one another.”

The Nutcracker premiered in Saint Petersburg in 1892, one week before Christmas, to mixed reviews. Though some praised the “astonishingly rich” score, others found the music too “somber and burdensome.” One reviewer lambasted the Waltz of the Snowflakes, decrying “the howling of a blizzard…. This waltz is closer to the Wolf’s Glen scene in Der Freischütz than to a children’s tale.”

Waltz of the Snowflakes

Perhaps this was the point. In scoring this seemingly innocent tale with weighty, even unsettling music, Tchaikovsky imbues the ballet with a complexity aligned with Hoffmann’s vision. Hoffmann wrote, “I think it is a great mistake to suppose that clever, imaginative children… should content themselves with the empty nonsense which is so often set before them under the name of Children’s Tales. They want something much better.”

A war-torn world

Hoffmann published his story in the wake of the Napoleonic Wars. Millions died in this global conflict that left the political landscape of Europe irrevocably changed. The portion of the ballet set in the Silberhaus home takes place in Nuremberg, Germany in the 1820s. Nuremberg was chosen for its association with toy making, but it was bankrupted and nearly invaded during the war. The mysterious godfather Drosselmeyer, missing an eye, alludes to wartime loss of life and limb, while the horde of invading mice serves as a reminder that conflict is never far away.

A young girl comes of age

During the battle between the mice and the toys, Clara throws a slipper at the Mouse King, allowing the Nutcracker to defeat him. As reward for her bravery, she is whisked away to Confiturembourg, the land of sweets. Her small act functions as a coming-of-age moment; by triumphing over evil, Clara proves that she is ready to grow up. Change and growth are necessary parts of life, as are love and companionship; Clara discovers all of these on her journey into the new and exotic land of Confiturembourg.

Though Clara is written to be seven years old, Stanislava Belinskaya, who premiered the role, was twelve at the time. Later productions deliberately make Clara older to add a subtext of burgeoning sexuality (Patricia Barker, who played Dream Clara in the filmed version of the Maurice Sendak production, was in her early 20s). In these depictions, her relationship to the Nutcracker/Prince becomes more than that of owner and plaything. Regardless of Clara’s age, the Nutcracker in doll form represents childhood while his transformation into a human prince represents her own transition to adulthood.

Apotheosis

The Nutcracker concludes with its heroine exalted. This final “apotheosis,” the glorification of a subject to divine status, features in several ballets, including Sleeping Beauty. Painters represented apotheosis with the divine character ascending to the heavens. In the George Balanchine production, Clara and the Prince fly away in a magic sleigh. Their destination is left ambiguous; is Clara returning home, or flying elsewhere?

Apotheosis

Other interpretations take a darker turn. In Hoffmann’s original, Marie is wounded during the battle with the mice and falls into a “deathlike slumber.” Some have posited that the cut became infected, causing her to hallucinate her toys coming to life. The infection proves fatal, and her imaginary friend Nutcracker, now an embodiment of Death, spirits her away to heaven.

A shocking death

Nine days after the premiere of his Sixth Symphony and less than a year after the opening performance of The Nutcracker, Tchaikovsky lay dead at the age of fifty-three. Officially, he was another casualty of the cholera epidemic that had been ravaging Saint Petersburg. To many, however, the death seemed suspicious. Numerous theories have since been proposed, including that the composer, depressed because of his feelings for his nephew, intentionally drank unboiled water. As part of this theory, many have interpreted the passionately mournful Sixth Symphony as a musical suicide note. Others have suggested that he was forced to kill himself with arsenic—on the orders of Tsar Alexander III, one scholar asserts—as punishment for his homosexuality.

Like most great art, The Nutcracker is more than what it appears on the surface. Its brilliance lies in its ability to be both a lighthearted confection as well as a profound meditation on childhood. For young children, the appeal of this perennial favorite may be found solely in the parade of sweets and dancers, but for adults, part of the ballet’s charm is its tantalizing promise of innocence.