Some pieces of music reveal new layers the closer you listen. Dvořák’s Songs my mother taught me is one of them: behind its gentle beauty lies a fascinating musical structure that makes memory itself audible.

View author's page

Reading time estimated : 4 min

When my old mother taught me to sing,

Strange that she often had tears in her eyes.

And now I also weep,

when I teach Gypsy children to play and sing.

A song between past and present

Dvořák’s Songs my mother taught me exists in a nebulous space. As the singer experiences a familiar rite from a different vantage point, his mind wanders from childhood memories to projections of the future. The passage of time and the passing down of a cultural tradition intertwine. Confusion leads to clarity.

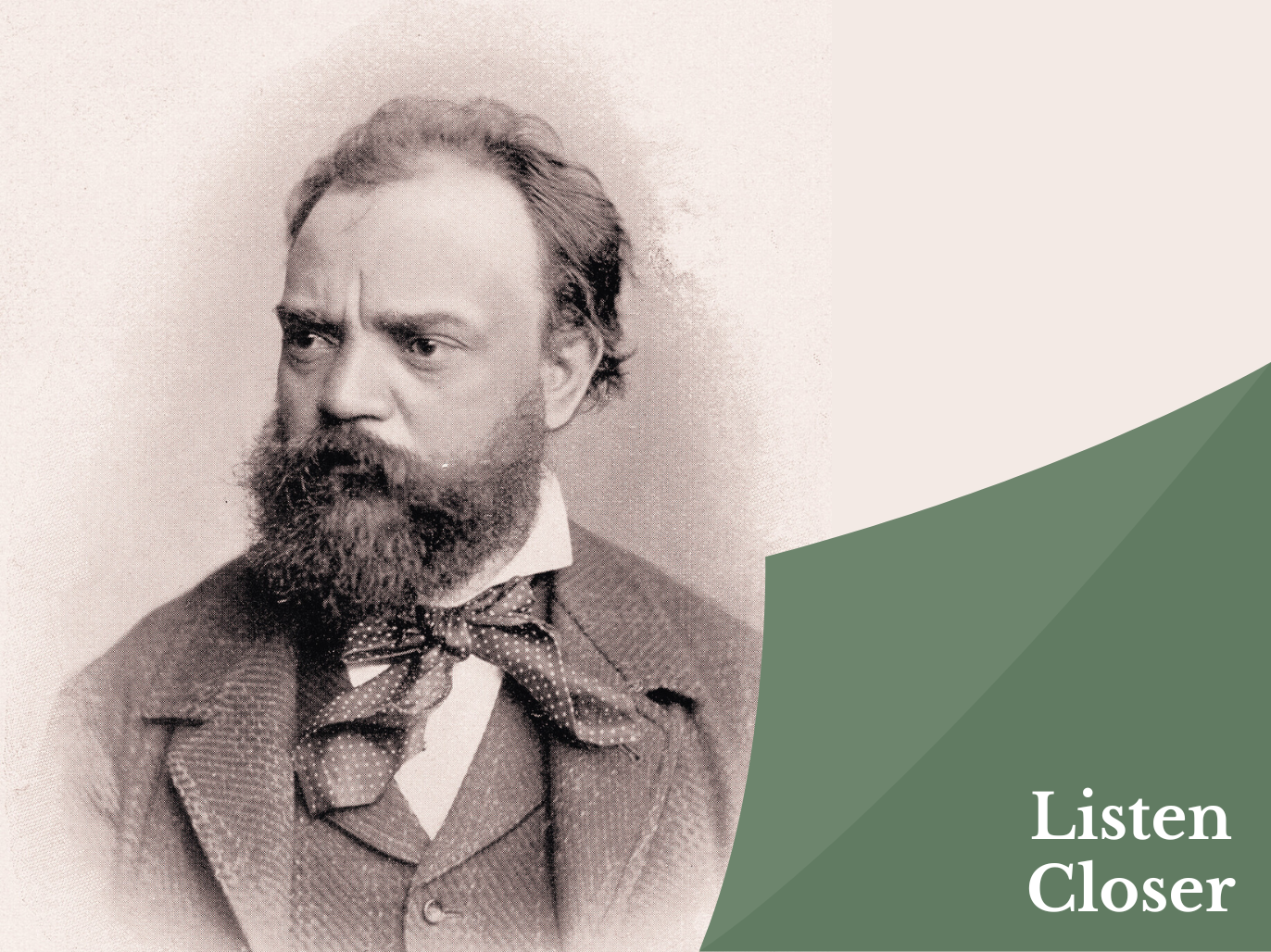

It’s all a lot to pack into just four lines of text and just over three minutes of music, but Czech poet Adolf Heyduk and composer Antonin Dvořák encapsulate the unstable emotional state brilliantly. It’s a fine line between the past and the present and sometimes our mind can get stuck in both at the same time.

Dvořák’s setting treats the two halves of Heyduk’s poem as parallel experiences: the melody he uses to treat the first two lines of text about the past is repeated a second time for the last two lines about the present. However, the second time we hear the melody, it’s more elaborate; Dvořák adds little vocal ornaments and embellishments, as though the singer has more confidence after having run through the tune already.

When rhythms diverge

Made up of small repeating fragments, the beautifully-spun melody takes us gently forward with simple repetition and gradual ascending step-wise motion before dropping us suddenly back with a few well-placed leaps down. Just when you think you’re on stable emotional ground, your heart jumps right into your throat:

But the most interesting—and extremely unusual!—technique Dvořák uses here to reflect the nebulous state of Heyduk’s poem is placing the singer and the pianist in two different yet complementary, time signatures. While the singer moves through the song in 2/4 time (that is, subdividing each measure into groups of two or four), the pianist’s line is in 6/8 (counting each measure in six). It’s a subtle enough strategy that you might not even be aware of what’s happening unless you have the score right in front of you, but the differences in how the two musicians break down each measure turn the song into a kind of hazy, ambiguous terrain: they’re perfectly in sync every few seconds at the top of each bar, but in between these shared sign posts, the rhythms move forward individually.

Let’s listen to the first minute of the song. First, listen to the lilting piano introduction, clearly in six (zero in on the rhythm in the left hand, if you have trouble counting it). Then, when the voice comes in, notice how the melody is much more square in rhythm, with the singer counting in two. The two musicians move along in parallel, outlining the same overall experience as their separate internal rhythms break it all down just a little differently.

The emotional melody floats over top a slightly unstable terrain, getting more clear the second time through—it’s a subtle technique, but just enough to convey the experience Heyduk drives at in his poem.

So the next time you listen to Songs my mother taught me, keep an ear out for the parallel internal clocks of the two musicians and try to observe how they ebb and flow alongside one another. Or just let Dvořák’s beautiful melody transport you straight into your own melancholy memories. The three-minute song has seen such success that it’s been adopted by voice types and instruments of all stripes—and it’s easy to see why.