When I first heard the opening passage of Kaija Saariaho’s Petals, it felt like someone had flipped a switch. The shimmering trill of a cello, slowly building in intensity, transformed the still air of my music classroom into a powerful soundscape far beyond my comprehension. At seventeen, I was familiar with the traditional repertoire—the instrument made me think of Bach’s Cello Suites or Elgar’s monumental Cello Concerto. But turning the pages of Saariaho’s score, I found that I had more questions than answers. Where was the key signature? Where were the bar lines? What did these arrows mean? What exactly was going on? The more I listened to the recording and looked at the notation, the more intrigued I became to discover the composer behind the work.

View author's page

Reading time estimated : 6 min

Who is Kaija Saariaho?

Kaija Saariaho (1952—2023) was a Finnish composer and one of the foremost artistic voices of her generation. A trailblazer in sonic expression and innovation, she studied at the Sibelius Academy in Helsinki and Hochschule für Musik in Freiburg, before moving to Paris to research at IRCAM (Institute for Research and Coordination in Acoustics / Music). Her music is known for blending classical instruments with electronics, creating a vast and distinct sonic palette with tone color (the quality of a sound) at its center. Saariaho’s prolific output spans five operas, several orchestral works, concertos, chamber and choral music pieces, and electroacoustic compositions. Lichtbogen for ensemble and electronics—inspired by the Northern Lights—served as a pivotal breakthrough in her career, showcasing her emerging style and marking the first time she worked with the computer in the context of instrumental music. Her debut opera L’Amour de Loin was an instant and immense success—with the recording earning a Grammy—and her symphonic works, including Oltra Mar and Orion, enjoy international acclaim to this day. Many of her compositions are described as “spectral”—a musical approach developed by a group of French composers in the 1970s, including Gérard Grisey and Tristan Murail.

What is Spectralism?

Spectralism uses sound spectra—the material qualities of sound interpreted by a computer—as the foundation for composition. An instrumental sound consists of the fundamental (the main pitch), but also of harmonic overtones (higher, more imperceptible sounds). The balance between the two affects tone color, and changes in this balance lie at the heart of Spectralism. For Gérard Grisey, Spectralism is “an attitude… It considers sounds, not as dead objects that you can easily and arbitrarily permutate in all directions, but as being like living objects with a birth, lifetime and death.”

Saariaho’s spectral works for solo cello

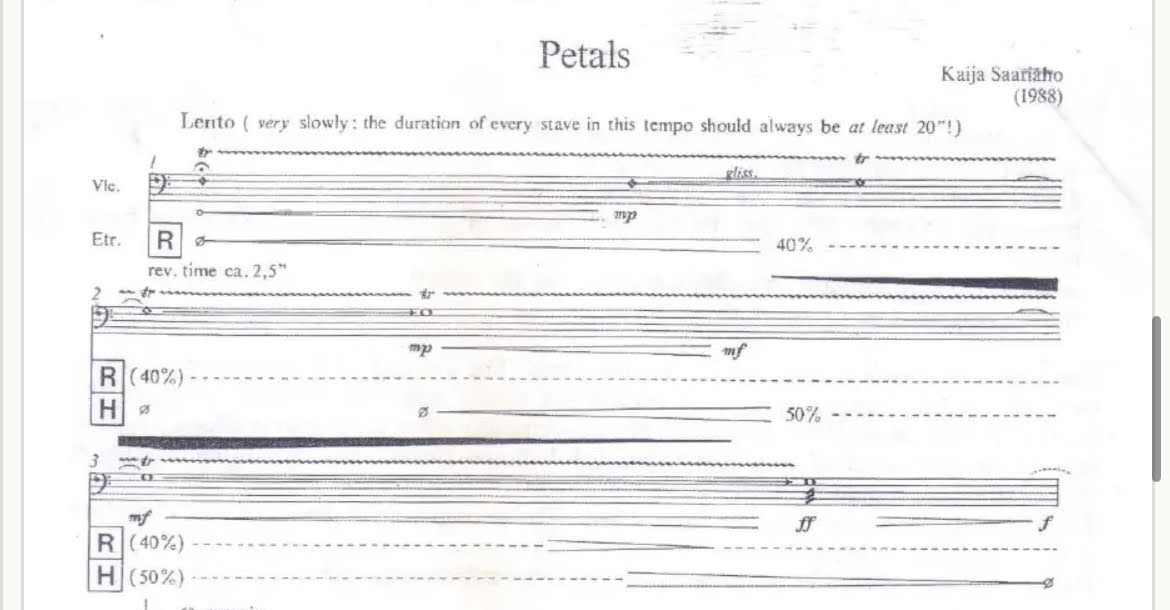

This scientific and analytical approach to composition greatly informed Saariaho’s works, particularly her earlier piece Petals. An offshoot of Nymphéa [Jardin Secret III] for string quartet and electronics, Petals is a virtuosic work for cello with optional electronics. Exploring immense contrasts in timbre, Saariaho uses extended techniques to transpose an acoustic instrument into a celestial, electronic atmosphere. The techniques are carefully conveyed through the score—horizontal arrows indicate a gradual change from one sound to another, square notes represent artificial harmonics, an increasingly thick black line highlights the need to add bow pressure to replicate a scratching sound. Specific percentages and time-stamps for harmonizer and reverb are likewise marked. The piece throws away the rulebook of functional harmony and traditional melodic ideas—instead, it focuses on the tension between “fragile coloristic passages” and “more energetic events with clear rhythmic and melodic character.” The transformation of sound is the central focus. A key signature and bar lines are no longer necessary in this context—the pace and sound quality are determined by the individual performer, making each interpretation unique.

Though Saariaho is potentially best known for her magnetic and awe-inspiring operas, she seems to gravitate to the cello for her instrumental works—after all, the instrument holds the full range of the human voice. Written immediately after L’Amour de Loin, Papillons for solo cello floats away from operatic dramaticism to a metaphor of the ephemeral: the butterfly. In a breathtaking concert from this year’s Festival Singer-Polignac, the seven miniatures unravel like a collection of sonic poems that flow seamlessly through the concert’s repertoire. Listen out for the delicate texture and harmonics which contribute to the expressive sound, right from the first movement. Papillons is much more lyrical than Petals, with fluttering motifs that contrast with warmer melodic lines, mirroring the unpredictable movements of a hovering butterfly.

Musical power and introspection: James Jolly in conversation with Kaija Saariaho

In a wonderful interview with James Jolly, Saariaho discussed her approach to composition. “When I compose, I don’t compose for other people,” she said. This might seem like a paradox: Doesn’t the performance of her work require an audience? But it’s what I find most compelling about her music. Saariaho’s mother recalls her asking to turn the pillow off at night when she couldn’t sleep — to turn off the music that animated her mind. This feeling never left, as Saariaho told Jolly that “I compose because I want to find a way to express this music that I imagine.” Saariaho’s music is always authentic because it comes from within. Once a work was complete, she made very few revisions—the written instructions to her pieces illustrate the clarity of her vision and purpose. Saariaho’s compositions open up the classical tradition, pushing its boundaries and defying their relevance. “[Music] doesn’t necessarily make the world a better place, but music can help people find different horizons within themselves…maybe it can give you new ideas to live your life as you would like to. Maybe music can change one person and maybe it can spread. All arts have a healing power if we take time to let it happen. I don’t put too much hope on it,” Saariaho told Jolly.

As long as performances and recordings of her music persist, I hold this hope. To listen to Saariaho is to enter another realm—a private world of unexplored possibilities which connects not to the expectations of listeners, but to their inner imagination. With this realization, Petals made sense to me. Detailed instruction and extended techniques replace conventional notation to bring the composer’s unique soundscape to life. Saariaho transformed the structural pillars of classical music to create a sound that is strikingly original and constantly evolving—this is her enduring legacy, the musical world she reshaped in her image.