In the early weeks of 1919, Danish papers were abuzz with speculation about a new production opening at the Royal Theatre. It was said to be one of the most extravagant performances staged in Denmark. Fyens Stiftstidende reported ‘the most amazing rumours’ about the production’s expenses being anything up to 1mn kroner, which roughly converts to being a cool $4mn in today’s currency. (Truthfully, it cost something closer to 240,000 kroner which, while not quite 1 million, was still an eye-watering amount for a single production.) The play was so long that it would be split over two nights, creating a theatrical extravaganza for Copenhagen’s audiences.

View author's page

Reading time estimated : 6 min

The play in question was Aladdin. The press furor was quite intentional. Up-and-coming director Johannes Poulsen had set out to make a splash with this production. He was one of a wave of directors across Scandinavia who tried to shake up theatrical culture in the 1910s. Copenhagen’s big theaters were relatively conservative, mainly staging historically accurate productions. Poulsen’s productions, however, were dazzling, flamboyant, and spectacular. As far as Poulsen was concerned, theaters needed to stop catering mainly for middle-class audiences, and start trying to have mass appeal. And to do that, they needed to be more — well, theatrical.

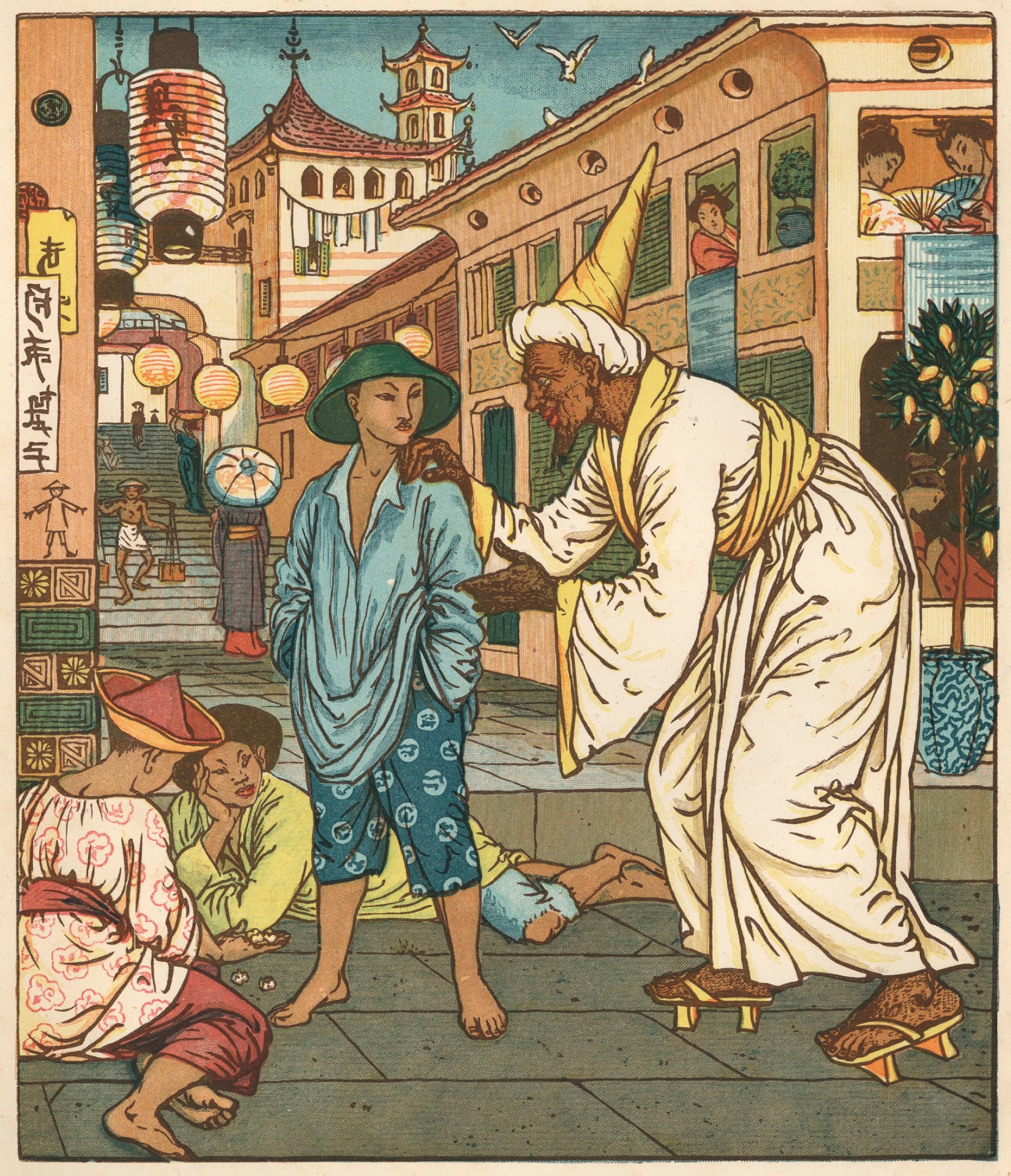

Aladdin was part of this rejuvenation project. The play was written by Adam Oehlenschläger, widely acknowledged to be one of Denmark’s most illustrious authors, retelling of the tale from the Arabian Nights. The story follows Aladdin, the poor son of a tailor, as he finds a magic lamp and with the assistance of a genie rises to become a Sultan. It’s full of spectacular set pieces (including a flying palace), dances, songs — everything that Poulsen was looking for in his campaign against realism.

Poulsen needed something to set his production apart as a trailblazing, modern staging. He selected a production team of some of the most prominent names amongst the Danish avant-garde. His choreographer was Emilie Walbom, the Royal Danish Ballet’s first woman choreographer. She had already created considerable controversy with her modern style, influenced by the Ballets Russes. Kay Nielsen was brought on board to provide the costumes. He’s better known now for his illustrations, and in 1917 when Poulsen started planning the production he was in the midst of illustrating the Arabian Nights, making him the perfect choice for Aladdin.

And for the music, Poulsen chose Carl Nielsen. The music was absolutely crucial. Theater music was big business in the early twentieth century — having a good score could make the difference between a production being a success or failure. At first, Nielsen was sceptical about accepting such a large commission as Aladdin, but Poulsen persevered. After a lot of cajoling from both Poulsen and the Theatre’s Artistic Director, Nielsen agreed to provide the music.

This is the version that’s most often performed today, but the original music was much more substantial. Nielsen’s Aladdin comprised not just dances, but also songs, and underscoring that played during both monologues and dialogue. Aladdin’s argument with the sorcerer Nureddin, for example, is accompanied by blasts from the orchestra between their lines, adding additional drama to Nureddin’s threats to lock Aladdin in the cave.

Despite his initial reservations, Nielsen seems to have been genuinely excited by Aladdin. While composing he wrote to his friend, composer and conductor Wilhelm Stenhammar, saying that “In a way I’m very excited by the effect and especially at certain places where we’ve made some experiments with several small orchestras etc.” The moment he’s referring to here is the music that was played during a market scene, which made its way into the orchestral suite as Number V, “The Market at Ispahan”. To create the feeling of a packed, busy market, Nielsen used four separate orchestras, all playing different music with different instrumentations.

Carl Nielsen, Aladdin Suite, Op. 34 – The Market at Ispahan.

Although he was enthusiastic about the scenario, Nielsen was furious with the final production. He objected to Poulsen’s cuts and alterations, as well as the directorial decision to remove the orchestra from the pit to make space for staging. Instead the orchestra were placed behind the scenes, which meant that the musical effect was not what Nielsen had had in mind. In fact he was so annoyed that he made the extraordinary move to release a statement to the Danish press, disassociating himself from the production entirely:

I must disclaim any responsibility for the musical side of Aladdin. As a result I have written to the Theatre Royal… indicating that I did not want my name displayed upon the programme or posters… and that only on this condition would I refrain from withdrawing my music.

Nothing eventually came of this disagreement – these kinds of spats were not unusual for big productions like this. But Nielsen did not work with Poulsen again. Nonetheless, Nielsen’s Aladdin score seems to have lingered in his mind. It is a significant influence on his later Fifth Symphony. Nielsen carried over many of the harmonies he had used for the theater score, as well as the idea of a conflict between good and evil, which Poulsen had decided to highlight in the play. In a publicity interview for the production, he said that he wanted to depict the young tailor as a symbol of goodness and luck against the “beastliness, wickedness, meanness” of the evil characters Nureddin and Hindbad, who try to murder Aladdin. This theme seems to have really chimed with Nielsen, so it’s perhaps unsurprising that ideas from Aladdin resurfaced in the symphony which he described as a “battle between evil and good”.

Theater was a hugely formative force for Nielsen. He started out his musical career as a violinist at the Royal Theatre, and he had served as assistant conductor for several years before being asked to compose the music for Aladdin. His extensive practical knowledge of how music worked in the theater meant that he was superbly well equipped to write theater music. He wrote music of some kind for around twenty plays, and continued to write for theater even after the Aladdin debacle. Nielsen’s Aladdin is a brilliant example of how deeply he understood the relationship between drama and sound — and his wonderful ability to weave drama into his music is part of what makes Nielsen’s work so compelling.