Before it became a Christmas tradition, Handel’s Messiah stirred controversy, inspired charity concerts, and even a royal standing ovation. This holiday season, uncover the surprising stories behind one of classical music’s most beloved works.

View author's page

Reading time estimated : 6 min

The Messiah was originally an Easter tradition

While today the Messiah may be seemingly inextricably associated with the Christmas season, it was originally an Easter composition. The piece was first performed in April 1742 and didn’t become a staple of the December repertoire until the nineteenth century.

Handel’s struggles in Dublin led to the Messiah’s first triumph

At the time of the premiere, Handel was down on his luck. His London opera company had folded, and he was suffering from health problems. Some researchers believe that Handel feared London audiences wouldn’t appreciate his unorthodox piece, but thought the sophisticated Dublin elite might. And he was right: the Dublin premiere was a resounding success! The audience of a record 700 people only fit because ladies had acquiesced to the management’s pleas that they wear dresses “without hoops” in order to make “room for more company”…

The first London performance of the Messiah caused a scandal

London audiences, on the other hand, were harder to win over… until Handel landed on the right venue. The Messiah‘s first London performance came 7 months after the Dublin premiere and caused a minor scandal, as audiences were not pleased to see such a sacred topic addressed in a theater.

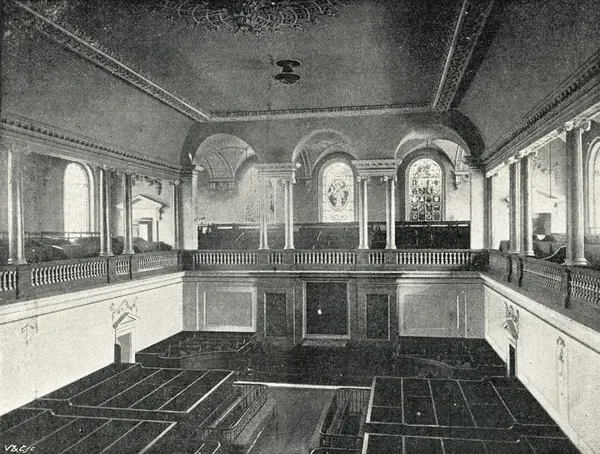

It wasn’t until 1750 that “Messiah fever” took hold after a performance in a decidedly different venue: the Foundling Hospital, one of the UK’s oldest charities for children. Handel would go on to conduct the Messiah in London twice a year, once as an annual benefit concert for the hospital, and once at Covent Garden (yes, Londoners came to terms with seeing the sacred piece in a theater!). Handel would also be named a governor of the hospital and leave it a copy of the score in his will.

The Messiah raised funds for charities long before It was popular

The Foundling Hospital was not the only organization to benefit from the Messiah‘s success and Handel’s generosity. As The Dublin Journal noted after its premiere, “It is but Justice to Mr. Handel, that the World should know, he generously gave the Money arising from this Grand Performance, to be equally shared by the Society for relieving Prisoners, the Charitable Infirmary, and Mercer’s Hospital, for which they will ever gratefully remember his Name.”

Handel composed the entire Messiah in just 24 days

Handel finished the over 250-page masterpiece in just 24 days in the summer of 1742, but that doesn’t mean the piece came to him without effort. Sarah Bardwell of London’s Handel House Museum has written that Handel “would literally write from morning to night.”

If you’d like to see physical evidence of the composer’s hard work, including alterations, references to the original cast of soloists, and more, Handel’s personal archival copy is available for perusal online at The British Library’s incredible Turning the Pages project! (Search for Handel.) You can also follow along with his progress throughout the 24 days: he noted the date each section was completed.

Handel faced criticism for the Messiah’s unconventional style

Despite the oratorio’s undeniable success, Handel’s setting of the text has not been without critique. Several instances of somewhat unusual word setting can be found in the Messiah, for example, placing the emphasis on the fourth syllable of “incorruptible” rather than the third. While some scholars have attributed this to Handel not being a native English speaker, others have chalked it up to a simple question of choice, noting that the composer had spent over 30 years in the UK by this point… Even the Messiah’s librettist, Charles Jennens, had his own criticism:

“[Handel] has made a fine Entertainment of it, tho’ not near so good as he might & ought to have done. I have with great difficulty made him correct some of the grossest faults in the composition, but he retain’d his Overture obstinately, in which there are some passages far unworthy of Handel, but much more unworthy of the Messiah.”

The tradition of standing for the Hallelujah Chorus began with a King

Ever wonder why we stand for the “Hallelujah Chorus”? The earliest reference to this unusual tradition dates back to the eighteenth century! Legend has it that when King George II first heard the work, he was so moved (or perhaps just stiff after sitting for several hours…?) that he stood up during the famous “Hallelujah Chorus” that closes Act II. When the King rises, all rise—and so a tradition was born! Or so the story goes, at least…

The “Hallelujah Chorus” has become a pop culture sensation

The iconic “Hallelujah Chorus” has even taken on a life of its own in popular culture, with its undeniable enthusiasm and joy used to great effect in movies, TV commercials, cartoons, flash mobs…

This now-infamous Christmas flash mob has been viewed over 57 million times!