An introduction to the series…

Welcome to chapter two of my medici.tv collaboration! You may have joined me over the summer when I helped co-present the live coverage of the Verbier Festival in Switzerland (which you can still see on catch-up). Joining Annie Dutoit-Argerich for the second week, we welcomed everyone from Sheku Kanneh-Mason to Paavo Järvi – on the best seat in the house, courtesy of our glass-fronted Studio VF nestled backstage between dressing rooms. Memorably this led to one broadcast featuring the background piano practise of one Evgeny Kissin, whose dressing room was next-door! You can imagine, it was musical paradise for a composer like me. Up close and personal with the world’s greatest musicians… which is also my aim in this new article series.

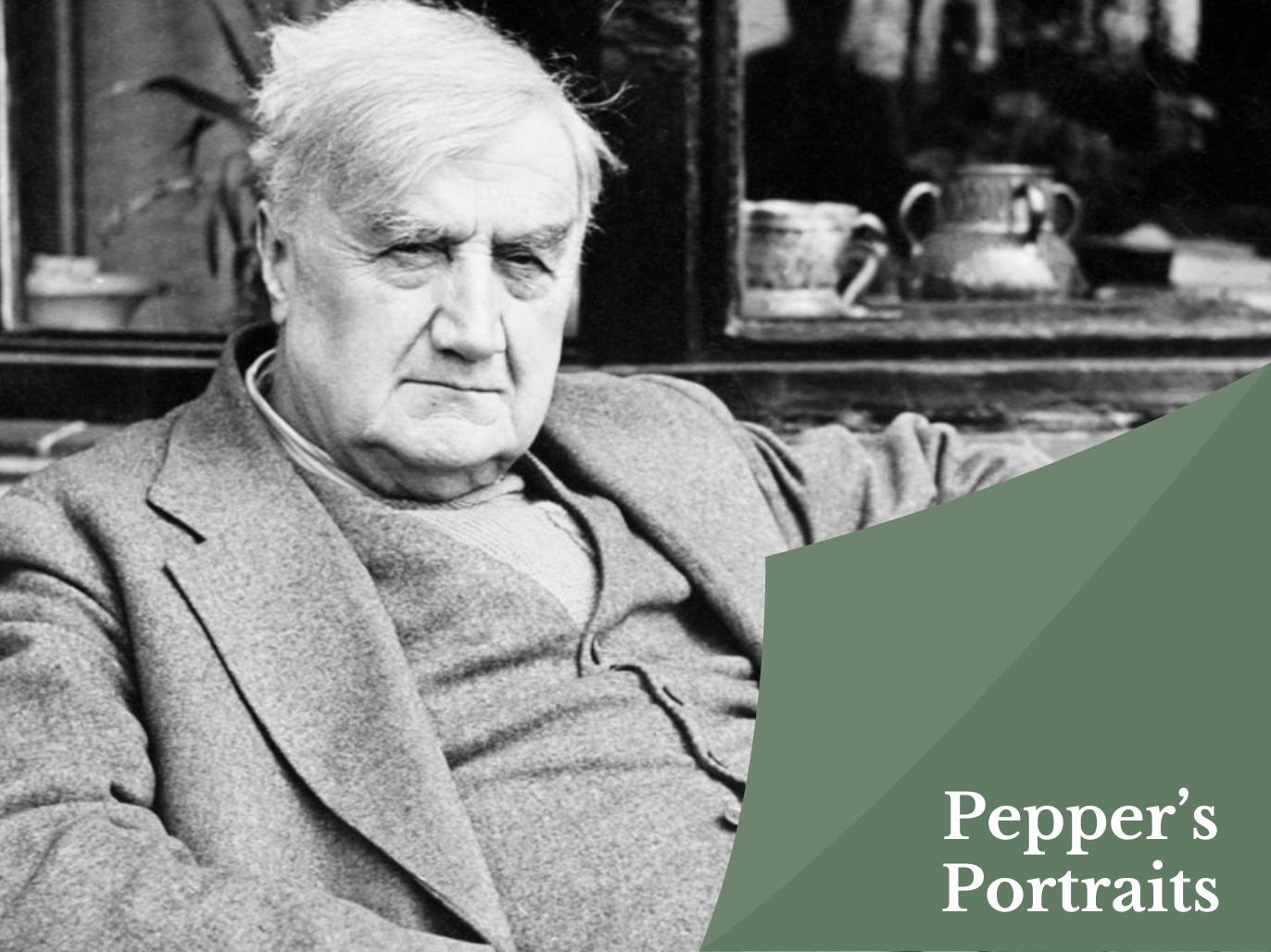

This is the impetus for our new Portraits series: putting some fabulous composers under a spotlight to present them as people, explore their role in the world… and perhaps shine a light on names or aspects of their work that deserve greater credit.

Cue, my first ‘Pepper Portrait’…