To celebrate the Halloween season, we delve into opera’s most villainous characters. Whether vengeful mothers or unrepentant lotharios, their naked ambition and lust for power generate thrills, disgust, and even sympathy. Heroes and ingénues may win our hearts, but sometimes it’s the bad guys who keep us coming back for more.

View author's page

Reading time estimated : 13 min

Mozart: Don Giovanni, from Don Giovanni

Richard Wagner, celebrated composer of Der Ring des Nibelungen and Tristan und Isolde, called Don Giovanni “the opera of all operas.” This darkest and most influential of Mozart’s operas remains a mainstay nearly 240 years after its premiere. With librettist Lorenzo da Ponte, Mozart transfigured the libertine archetype of Don Juan into an elevated dramma giocoso (literally “drama with jokes”).

At the opera’s unforgettable climax, the murderous, womanizing Giovanni has jokingly invited to dinner a graveyard statue commemorating one of his victims. Accepting the summons, the living statue offers Giovanni one final opportunity to repent. When he refuses, the statue and a chorus of demons carry him down to Hell. The concluding ensemble delivers the opera’s moral: “Such is the end of the evildoer,” those who knew Giovanni sing. “The death of a sinner always reflects his life.”

Gounod: Méphistophélès, from Faust

Goethe’s magnum opus, Faust, has long inspired composers (one of my favorite musical depictions of the Faust legend is Franz Schubert’s incredible song “Gretchen am Spinnrade,” which he composed at the age of 17). Across songs and symphonies, oratorio and opera, Faust’s deal with the devil leaves audiences asking, “What do I want, and what would I do to get it?”

Gounod’s Faust (1859), his fourth of twelve operas, remains his most popular. In this Royal Opera House production, bass-baritone Erwin Schrott portrays the diabolical Méphistophélès. In “Le veau d’or,” one of the demon’s most famous arias, he provides a crowd with wine and sings a rousing, irreverent song about the Biblical golden calf.

Verdi: The Duke of Mantua, from Rigoletto

With suave, high-flying arias like “Questa o quella” and the tremendously catchy “La donna è mobile,” (so catchy, in fact, that Verdi refused to reveal it to the cast until the final rehearsals in order to keep the tune secret), the lecherous Duke of Mantua proves that not all tenors are heroes. In Verdi’s gripping drama Rigoletto (1851), the physically disfigured titular jester and father—a baritone role—claims more sympathy than the romantic tenor lead. The Duke’s conventional, tuneful arias project both charm and shallowness.

Verdi composed the score to Rigoletto in six weeks, undeterred by the Venetian government’s threats to ban the “disgusting” and “obscene” libretto. The opera was an immediate success, the canals of Venice filled with the voices of gondoliers singing “La donna è mobile.” Rigoletto has since become a mainstay of the standard repertory

Handel: Alcina, from Alcina

Handel’s Alcina (1735) shows not only that villains can be women, but that they can be complex characters capable of both love and hate, elation and grief. Alcina, a sorceress who ensnares men on her enchanted island and transforms them into plants, animals, and even stones, has newly bewitched the knight Ruggiero. When Ruggiero’s fiancée arrives to rescue him, Alcina attempts to prevent his escape using witchcraft. Realizing, however, that her love for him is true, her dark magic fails. In this moving scene, we see the beginning of Alcina’s undoing as the once-formidable sorceress is reduced to pleading with her powers, her impotent cries of “perchè” (“why?”) echoing across the island.

Gershwin: Sportin’ Life, from Porgy and Bess

Porgy and Bess (1935), George Gershwin’s sole opera, depicts the denizens of the fictional Catfish Row in Charleston, South Carolina. Its all-Black cast was a milestone of representation, and the 1952 touring production launched the career of the great American soprano Leontyne Price. The unscrupulous drug dealer Sportin’ Life, who ultimately steals Bess away to New York, delivers the aria “It Ain’t Necessarily So.” Gershwin borrowed from Jewish liturgical music to shape its slinking chromatic melody.

Since the opera’s premiere 90 years ago, several of its numbers, including “It Ain’t Necessarily So,” have become standards of the Great American Songbook. Some of the century’s greatest artists including Aretha Franklin, Sarah Vaughan, Louis Armstrong, and Ella Fitzgerald, have covered the song; Jascha Heifetz, a friend of Gershwin’s, wrote a transcription for violin. It even became a symbol of anti-fascist resistance during the Second World War. The Nazis banned performances of Porgy and Bess during their occupation of Copenhagen. In response, each time the Nazis sent victory communiqués over the radio, the Danish underground cut in with a recording of “It Ain’t Necessarily So.”

Monteverdi: Nerone, from L’Incoronazione di Poppea

The Roman Empire has long inspired composers and librettists. From Handel’s Giulio Cesare to Mozart’s penultimate opera, La Clemenza di Tito, the political intrigue of these larger-than-life characters, combined with deeply human emotions and flaws, continues to fascinate. Claudio Monteverdi, the oldest composer whose operas are still regularly performed, drew on the history of the infamous emperor Nero for his final opera, L’Incoronazione di Poppea (1643). In this tale of lust and power, the corrupt emperor forsakes friends and family in pursuit of his consort, Poppea.

After banishing his wife, Nero weds Poppea and she is crowned empress. Poppea concludes with the pair singing one of Baroque opera’s most tender duets, “Pur ti miro, pur ti godo.” A descending four-note figure (tetrachord) in the bass signifies amorous love; the push and pull of the lovers’ vocal lines is equally suggestive. These proclamations of love, set to Monteverdi’s rapturous music, belie the real-world counterparts’ ultimate fate: Poppea died shortly after their marriage, possibly at her husband’s hands, while he committed suicide a few years later.

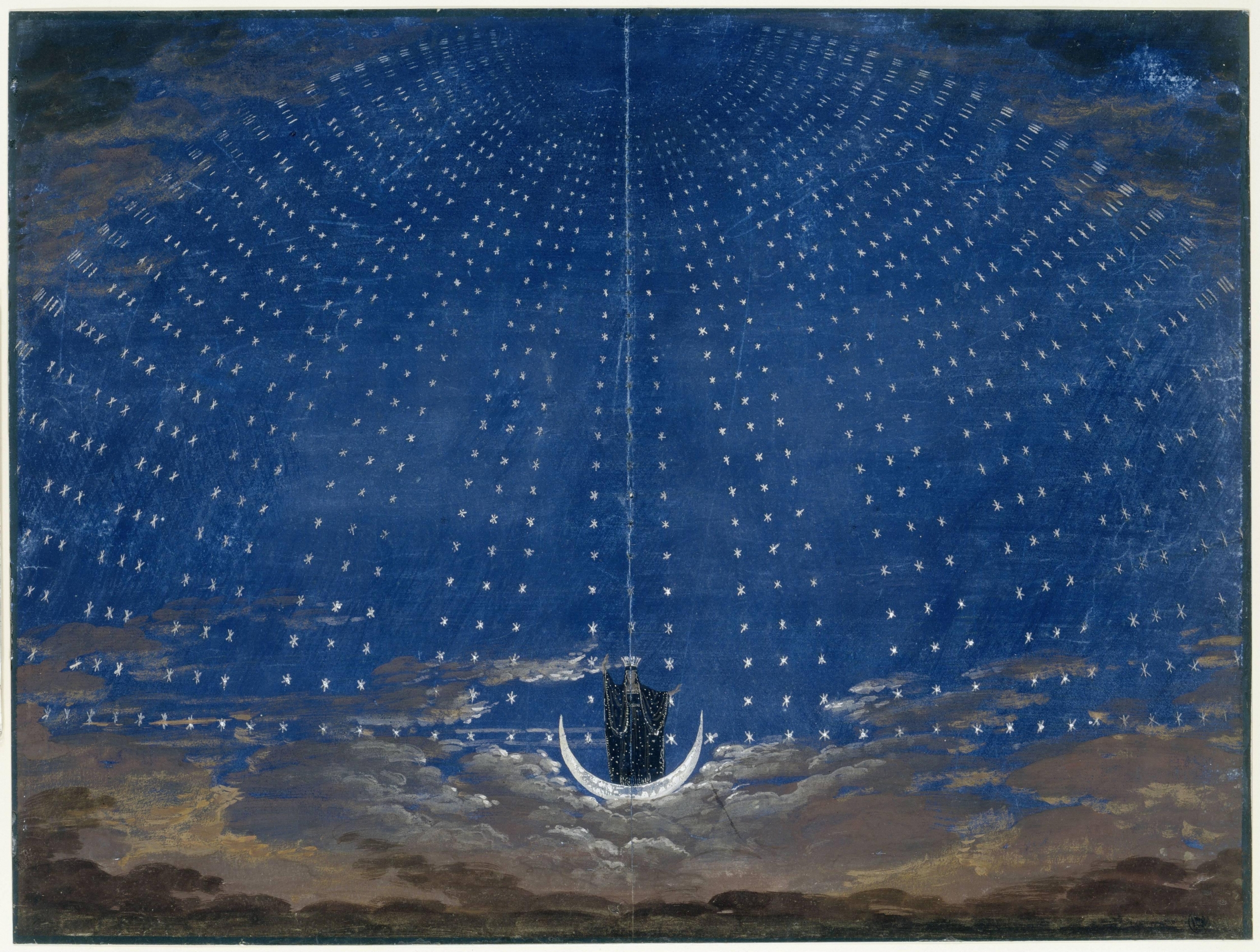

Mozart: Queen of the Night, from Die Zauberflöte

Mozart’s final opera, Die Zauberflöte (1791), premiered just two months before its composer’s death at the age of 35. He wrote the role of the malevolent Queen of the Night for his sister-in-law, Josepha Hofer. Though she has only two arias, the role is one of the most difficult in the soprano repertoire, demanding a wide range and vocal agility.

In this rage aria, the Queen places a knife into her daughter Pamina’s hand and exhorts her to assassinate her rival, Sarastro. As in his earlier opera, Die Entführung aus dem Serail, Mozart uses coloratura not for mere display but to reflect the character’s resolve and anger. The aria requires multiple high Fs, the highest note in the standard repertoire. In 1977, the aria literally went sky-high when it was selected for inclusion on the Voyager Golden Record project. NASA launched recordings of sounds and music from around the world into deep space; Mozart’s “Queen of the Night” aria holds the honor of being the only opera selection included on the Record.

Puccini: Scarpia, from Tosca

In 1964, legendary soprano Maria Callas came out of semi-retirement to perform the title role of Puccini’s Tosca (1900) at the London Royal Opera House. The production, directed by Franco Zeffirelli, co-starred Tito Gobbi as Baron Scarpia, Rome’s sadistic chief of police. Callas and Gobbi’s performance of the electrifying Act II confrontation, captured in this video, remains one of the most famous recordings in opera history.

In this scene, Tosca hears her lover, Cavaradossi, being tortured. Unable to bear his anguished cries, she betrays the location of the fugitive Angelotti to Scarpia, who promises to set Cavaradossi free if Tosca will go to bed with him. In his aria “Se la giurata fede debbo tradir,” Scarpia switches between authoritative, declamatory singing and grossly seductive legato lines. Following her aria “Vissi d’arte,” the act ends with Tosca plunging a knife into Scarpia’s chest, crying, “This is the kiss of Tosca!” and placing a crucifix upon his bloodied corpse.

Beethoven: Don Pizarro, from Fidelio

Beethoven began composing his “rescue opera” Fidelio (1814) in 1804, fifteen years after the storming of the Bastille, the flashpoint of the French Revolution. Beethoven drafted numerous revisions (he composed no fewer than four iterations of the overture alone, including this version performed by the West-Eastern Divan Orchestra) and paused to write other works including the Fifth through Eighth Symphonies. Indeed, he bitterly remarked to a friend that the opera, his first and last, would “win [him] a martyr’s crown.”

Set in a Spanish prison, the opera recounts how Leonore, disguised as a guard named “Fidelio,” rescues her wrongfully incarcerated husband from death. Standing in her way is the despotic prison governor Pizarro. In this declamatory Act I aria, Pizarro gloats at the chance to eliminate his rival once and for all.

Verdi: Iago, from Otello

Giuseppe Verdi, an ardent admirer of William Shakespeare, completed three operas based on the Bard’s plays. The second of these, Otello (1887), may be his best. Propelling this timeless tale of jealousy and revenge is one of literature’s greatest villains: Otello’s treacherous standard-bearer, Iago. Driven by his hatred and jealousy, Iago schemes to turn Otello against his wife, Desdemona. Shakespeare scholar A. C. Bradley wrote that Iago “stands supreme among Shakespeare’s evil characters because the greatest intensity and subtlety of imagination have gone into his making.”

Iago reveals his theology in his Act II aria “Credo in un dio crudel.” The text, by librettist Arrigo Boito, has no counterpart in Shakespeare’s original. Verdi initiates the aria with sinister brass fanfare, its hollow unison reflecting the emptiness of Iago’s soul. “I believe in a cruel God,” he declaims, “who has created me in his image and whom, in my anger, I name.” Verdi so favored the dark, powerful baritone voice exemplified in Iago that it gained the nickname “Verdi baritone.” Other roles demanding this stentorian voice type include the title characters of Verdi’s Rigoletto, Macbeth, and Falstaff.

What unites the great villains of opera?

On the surface, the motivations of opera’s most nefarious characters seem as different as the stories that birthed them. What could a love-struck sorceress and a small-time drug dealer possibly have in common? Yet whether they seek lust, revenge, or riches, all of these villains are, at their core, on a quest for power. When that desire for power manifests as domination over others, tragedy is never far behind.