I’ve been going to concerts since my mid-teens, yet stepping into a new (to me) hall is still a thrilling experience. There are those temples to a long performing tradition, the ‘shoebox’ halls like Amsterdam’s Concertgebouw or Boston’s Symphony Hall, that deliver a near-ideal acoustic and have allowed the resident orchestras to develop a glorious sound and personality. Then there are the halls that make an architectural statement, like Frank Gehry’s Walt Disney Concert Hall or Hans Scharoun’s still-striking Philharmonie in Berlin – both outside and in – where the players and audience are brought together in a remarkably intimate balance (and Tokyo’s Suntory Hall, clearly inspired by Berlin, combines the same feeling with an even more perfect sound – Pavarotti, it was said, would rehearse longer there than anywhere else simply because he loved the acoustic).

View author's page

Reading time estimated : 7 min

Then there’s a hall I’ve become a huge fan of over the past few years (and, happily, within easy reach by train from my home city, London): the Philharmonie de Paris. Jean Nouvel’s striking creation is, hard to believe, entering its second decade as the city’s main orchestral concert hall, and its sound is beautifully analytic yet warm – a combination I find very appealing. It also feels wonderfully contemporary: its asymmetric design and organic curves fall very easily on the eye.

Every time I attend a concert there, I’m struck by how different the audience is from just about any other worldwide – markedly younger and patently hungry for music. (That may, of course, be the effect Klaus Mäkelä has had on the orchestral scene through his leadership of the Orchestre de Paris and his imaginative programming.)

Maestro Klaus Mäkelä and the Orchestre de Paris perform Tchaikovsky’s Symphony No. 6 at the Philharmonie de Paris

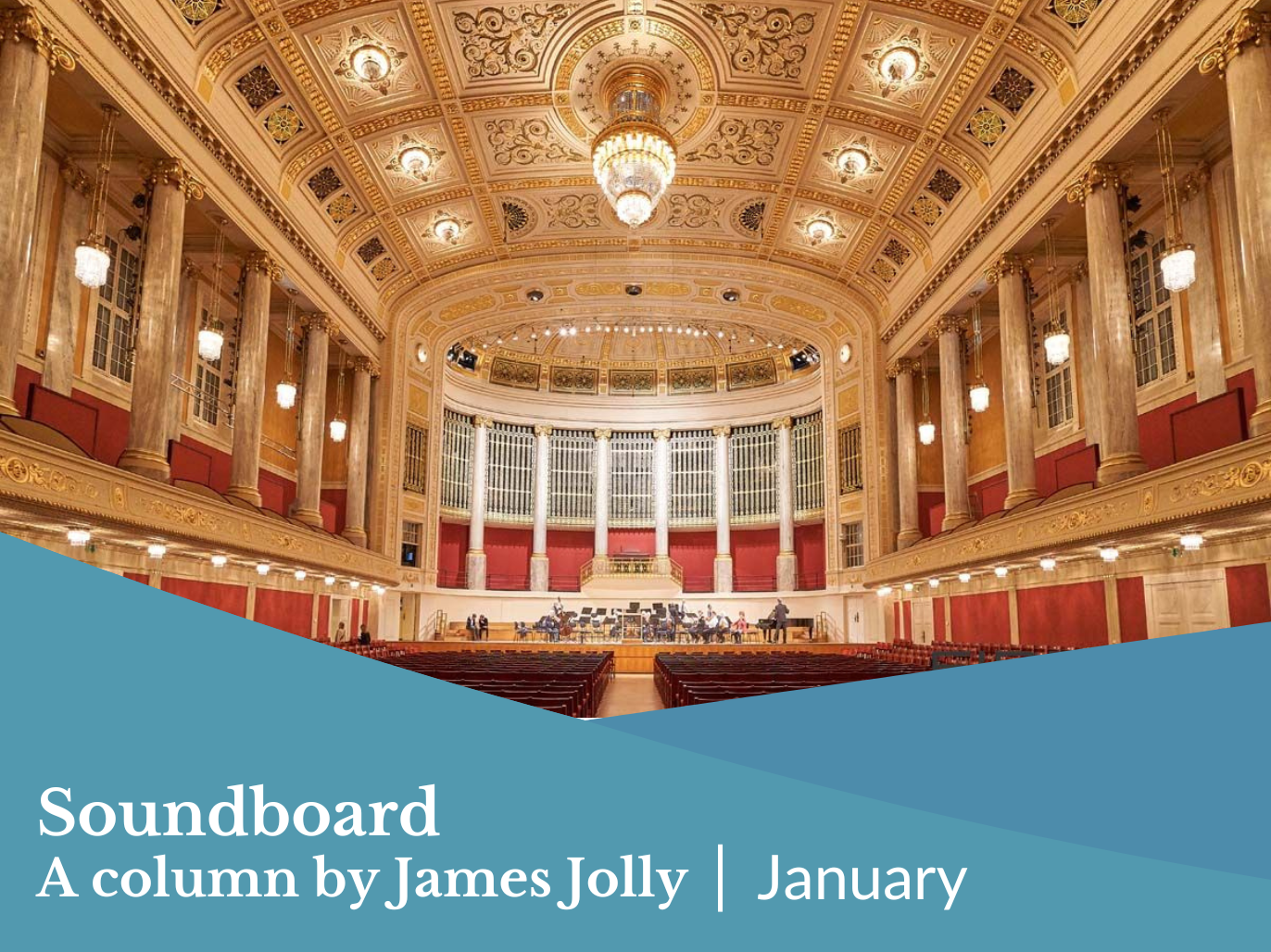

Now, I’ve added another concert hall to my list of memorable settings for music: Vienna’s Konzerthaus. In the city for a few days, I ticked off three ‘firsts’ from my wish list: attending a concert here, hearing the Vienna Symphony Orchestra live, and seeing Philippe Jordan conduct a symphonic concert (rather than an opera). So, on a very cold January Sunday night, I went to hear Jan Lisiecki play Mendelssohn’s First Piano Concerto, followed by Jordan conducting a fine Bruckner Fourth.

For viewers on medici.tv, neither the orchestra nor the venue will be novelties (and there are many concerts available to watch featuring visiting ensembles), so it was good to discover that the Konzerthaus is not only as visually striking and gilded as its more celebrated neighbour, the Musikverein, but also has an acoustic that genuinely adds something special to an already fine orchestra. It blends the sound to great effect (the Bruckner had colossal power as well as clarity), yet allows each section to emerge from the overall sound picture with detail. The natural horns, favoured by the Vienna Symphony, take a moment to get used to, but the strings sounded gorgeous (the violas, seated next to the first violins, particularly so), and the double basses – placed in three rising pairs with two more alongside – gave the bass of the orchestra a wonderfully focused and very powerful heft that balanced the timpani on the other side of the stage.

To hear more from the Vienna Symphony Orchestra in their Konzerthaus home, discover this concert with Lahav Shani and Martha Argerich in Prokofiev and Rachmaninov:

Hearing an orchestra in its own hall is always a treat, because the acoustic has nearly always helped shape its style and sonority. To take a supreme example, the Concertgebouw – the hall – may present its challenges to the players, but to the audience the effect is heavenly. And when you hear a work that an orchestra has in its DNA – which, in Amsterdam, might be a symphony by Mahler – you are not only struck by the ‘rightness’ of it all, but you also feel as though you are connecting with the composer himself. Mahler conducted this orchestra, in this hall, and somehow that experience seems to have filtered down through generations of orchestral players.

The Vienna Symphony was founded in 1900 and has been at home at the Konzerthaus since the hall was built in 1913. Despite the international renown of the Philharmonic, the Symphony has worked with many great conductors over the years. Rather like London’s Philharmonia, it was an ensemble on which Herbert von Karajan – who never held an official title with either group – made his mark in the 1950s. Subsequently, it worked with Hermann Scherchen, Wolfgang Sawallisch (the longest-serving chief conductor of the post-war years), Carlo Maria Giulini, and many others.

Philippe Jordan was in charge between 2014 and 2021, and his impressive musicianship is well illustrated by the cycle of Beethoven symphonies he recorded with the VSO. There was certainly a sense of homecoming in the rapport he shared with the players on his return to the podium to work with them once again.

Hearing a ‘new’ orchestra in an unfamiliar setting elicits a different response from the listener. First comes a quick verdict on the orchestra’s personality: here, beautifully silky strings, some characterful winds (nicely illustrated in the slightly avian twitterings of the Scherzo), and a firm, resonant bass that underpinned the ensemble’s overall sound. It was slightly unusual to hear the Mendelssohn piano concerto played with such a large body of strings, but their attack and phrasing were razor-sharp and felt very much of our time – there was absolutely no sense that the band was carrying any extra weight. Everything was wonderfully precise and punchy; they provided a perfect foil to Lisiecki’s elegant, sparkling playing and his imaginative and characteristically poetic approach to the music.

Then there was the hall itself – lovely to look at and generous in what it gives back. The wide stage, filled from side to side, with the curved wall behind it, pushed the sound outwards in a blended yet textured stream that sounded very impressive fourteen rows back in the parterre. It was an acoustic I’d previously encountered only on record, and one in which some classic recordings were made. (I’ve long cherished Giulini’s Bruckner Eighth – albeit made with the Vienna Philharmonic – and the Konzerthaus clearly played its part.)

So, if I had made a New Year’s resolution to add a new concert hall to my listening experience, I’d have ticked that box very early in 2026. It’s now filed away in my musical memory, and having heard it at first hand (and experienced a far more local, enthusiastic and knowledgeable audience than at the Musikverein), I’ll watch concerts filmed there with a different and more informed attention. The next new hall on my list for 2026 is Montreal’s Symphony House, home of the Montreal Symphony, which I’ll visit for the first time in April.