It may be the most glamorous waltz in the world but the Blue Danube’s story begins with a national crisis, disastrous lyrics about street lamps, and a composer muttering that only the coda was worth keeping… Today it is one of the hallmark moments of the Vienna Philharmonic’s iconic New Year’s Concert, broadcast around the world. Its journey from fiasco to global icon is one of classical music’s unlikeliest stories.

View author's page

Reading time estimated : 7 min

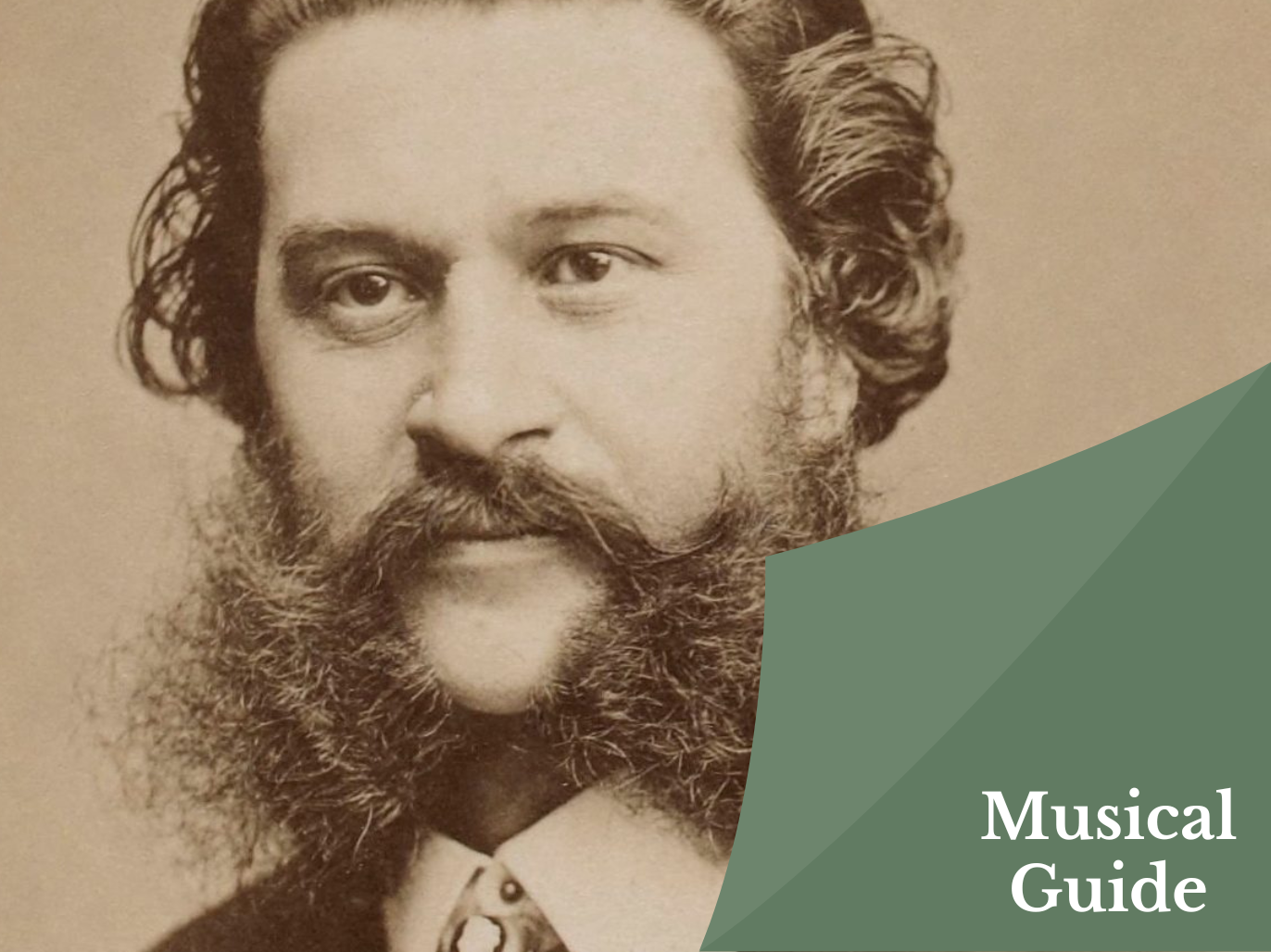

1. Born in Defeat

In 1866, Austria had just suffered a crushing defeat against Prussia at the Battle of Sadowa (Königgrätz). The Habsburg Empire watched its dream of dominating the German Confederation crumble. In this gloomy context, Johann Strauss II, then 42 years old, received a commission from the director of the Vienna Men’s Choral Association. His mission was to compose a “lively and joyful choral waltz” to lift the nation’s spirits. The result would be anything but joyful—at least at first.

2. Catastrophic Lyrics About… Street Lamps

The choir’s designated “poet,” Joseph Weyl, was actually a police clerk. His first draft of lyrics? A satirical ode to the new electric street lamps installed at Vienna’s intersections. The choir refused to sing such nonsense! Weyl then proposed a second version about Carnival and the depressed mood of the capital. These lyrics, deemed ridiculous by some and provocative by others, contributed to a lukewarm reception on opening night, February 15, 1867. Strauss himself was reportedly so disheartened by the failure that he quipped: “The devil take the waltz! My only regret is the coda.”

3. The Parisian Triumph: 20 Encores

Three months later, everything changed. Invited to the Austrian embassy during the Paris World’s Fair, Strauss had his score shipped from Vienna and rearranged it for orchestra alone—without the disastrous lyrics. When this new version was performed on May 28, 1867, it was a sensation with over 20 encores. In the months that followed, sheet music sales reached one million copies worldwide. Viennese publishers struggled to keep up with demand. The “Danube Waltz” instantly became a global hit, and Strauss was crowned the “Waltz King” in Paris.

4. The Danube Is (Almost) Never Blue

In 1903, legal counsel and hydrographer Anton Bruszkay decided to record the river’s colour every morning for a year. His findings: “Brown 11 days, clay yellow 46 days, dirty green 59 days, grass green 5 days, steel green 69 days, emerald green 46 days, and dark green 64 days.” …over 300 days when the Danube was not blue. Hydrologists explain that water colour depends on suspended particles and algae presence. What can science do, however, against the power of collective imagination? Strauss’s title may have been inspired by the Hungarian poet Karl Isidor Beck, who mentions the “beautiful blue Danube” in his verses.

5. Brahms’s Envy: “Alas, Not by Me!”

The greatest composers of the era admired Strauss deeply, and none more than Johannes Brahms, himself a composer of waltzes. At a ball, a lady reportedly asked him for an autograph. Brahms inscribed the opening measures of the Blue Danube on her fan, adding the now-famous annotation: “Alas, not by me!” (“Leider nicht von mir”). Richard Wagner observed that audiences were literally “intoxicated” by Strauss’s music. Berlioz summed it up: “Vienna without Strauss is like Austria without the Danube!”

6. Boston 1872: 1,000 Musicians and 100 Conductors

In 1872, Strauss crossed the Atlantic for the World’s Peace Jubilee in Boston, a mammoth festival celebrating the end of the Franco-Prussian War. America did nothing by halves: organizers erected a wooden “Colosseum” to hold 100,000 spectators. On stage, no fewer than 1,000 musicians and 20,000 choristers performed. Strauss, perched on his podium, communicated through 100 assistant conductors. After the concert, he confided: “I gave my signal, my hundred assistant conductors followed as best they could, and then broke out an unholy row such as I shall never forget.” For this 17-concert tour, Boston paid him the astronomical sum of $100,000 (equivalent to several million today).

7. Kubrick and Space: A Happy Accident

In 1968, Stanley Kubrick revolutionised cinema with 2001: A Space Odyssey. The scene of spacecraft waltzing in orbit to the strains of the Blue Danube has become iconic. This audacious pairing, however, owes much to chance: a technician had put the record on as background music while the crew watched rushes in the editing room and Kubrick realised the music “fit perfectly.” Composer Alex North, hired to write an original score, only discovered at the premiere that Kubrick had entirely discarded his work. The recording heard in the film is conducted by Herbert von Karajan with the Berlin Philharmonic.

8. The Anthem of Austrian Rebirth (1945)

On April 27, 1945, Austria proclaimed its independence after seven years of annexation by Nazi Germany. There was just one problem: the country no longer had a national anthem. In front of Vienna’s Parliament, the Blue Danube filled the silence, celebrating the Republic’s rebirth. The Austrian national football team also adopted it after the war. It wasn’t until October 1946 that Austria acquired an official anthem (set to a melody attributed to Mozart). Strauss’s waltz, however, is still considered to this day the country’s “second national anthem.” Austrian Airlines passengers can hear it at takeoff and landing.

9. The New Year’s Concert: A Tradition Born in Wartime

The first New Year’s Concert took place on December 30-31, 1939, in annexed Austria. Conductor Clemens Krauss proposed a programme entirely devoted to the Strauss dynasty to “boost morale.” In 1941, the event moved to New Year’s morning. Since 1958, the concert has ritually concluded with two unchanging encores. First comes the Blue Danube, whose introduction the audience traditionally interrupts with applause as the conductor wishes everyone a happy new year. Then follows the Radetzky March, during which the audience claps along. Broadcast in 90 countries, the concert draws millions of viewers each year.

10. Destination Space: Waltz into Space (2025)

To celebrate the bicentenary of Johann Strauss II’s birth (1825-2025), the Vienna Tourist Board and the European Space Agency (ESA) launched the “Waltz into Space” project. On May 31, 2025, the Cebreros station in Spain transmitted the Blue Danube into the universe as electromagnetic waves. The signal reached the Voyager 1 probe approximately 23 hours later, correcting a “historical oversight:” the waltz was notably absent from the famous Golden Record launched in 1977.