Picture this. A soft fade onto the image of a slim, white-haired conductor on the right-hand side of the frame, waist up only, our eyes thus drawn to his supple, outstretched arms coaxing out the first piano bars of Beethoven’s “Pastoral” Symphony No. 6. Our view of the orchestra itself is limited, but impactful: three outer-desk cellists, soft focus, forming a raked line in the background; then suddenly, a bank of even blurrier violin bows leaping into the foreground so that now conductor and cellists are observed as if through long grasses dancing in the wind. Onwards, and orchestral sections will be captured directly sidelong, as though looking down a military formation; instruments will be watched from unusual viewpoints (a line of violin backs on shoulders), and dramatically lit (choice glints on shadowy double basses). Always, the camera will land on the next melody-carrier with time to prepare the viewer’s ear and build suspense. Not once, symphony-long, will we see a direct long shot showing the entire orchestra and conductor.

View author's page

Reading time estimated : 11 min

Excerpt from Beethoven’s “Pastoral” Symphony No. 6

Karajan’s cinematic vision

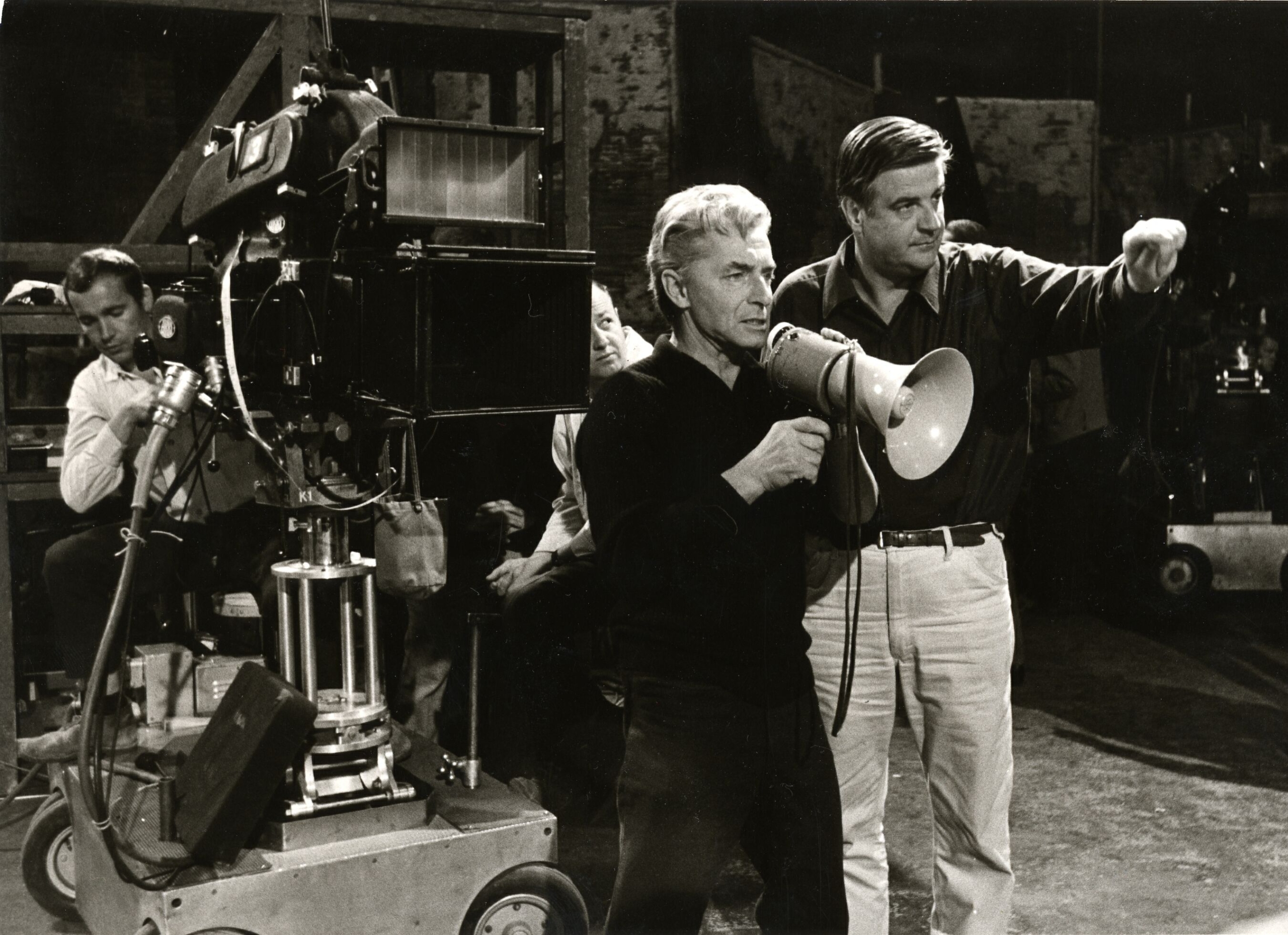

All in all, it’s a ground-breakingly daring and modern way to film a Beethoven symphony. Yet it is Herbert von Karajan (1908-1989) conducting the Berlin Philharmonic in the mid-late 1980s – part of a huge, late-life project with the Berlin and Vienna Philharmonics which saw him create a filmed library of his core symphonic and operatic repertory, intended as an enduring musical resource for the coming generation of DVD collectors. What was more, while this was Karajan’s final filmed “Pastoral”, as far back as 1967 he had collaborated with experimental film director Hugo Niebeling for an arguably even more visually striking account, its own effects including the stage floor illuminated from beneath the musicians’ feet. Meanwhile in the operatic field, he filmed with a string of celebrated stage and film directors, among them Franco Zeffirelli, most famously for a 1965 film of Zeffirelli’s La Bohème for La Scala in Milan, Karajan conducting while Zeffirelli’s cameras placed the viewer right in the middle of the set, walking among its cast.

Excerpt from Puccini’s La Bohème

Matthias Röder has been CEO of the Karajan Institute since 2011. “When I first took over the institute”, he remembers, “Karajan had sort of become an icon for people who have a very conservative view of how classical music should be. Yet this was something I could not equate with everything I saw in the archive. Not least the music films he made. His 1967 “Pastoral” Symphony would have been nothing short of shocking to its first audiences.”

A technophile before his time

In audio recording alone, Karajan was a determined and knowledgeable pioneer, pushing the latest technology from very early stereo, to multichannel recordings, to the development and promotion of the compact disc. His industry influence upon the latter was seismic, bringing its four co-developer companies to Salzburg in 1981 to present it at an international press conference, then himself recording one of the very first CDs (Strauss’s Alpine Symphony) and setting up a CD manufacturing plant in Salzburg. Decades before the CD, his fascination with frequency spectrums, and pursuit of the widest possible dynamic range – with the greatest clarity at its extremes – saw him constantly push his studio engineers beyond what they had thought possible. He refused to compress, hence why you can’t successfully listen to even his oldest recordings in a car without having to constantly adjust the volume.

In film, he was at least as visionary, foreseeing the future of classical performance as a multimedia experience, then helping create it while setting artistic standards that even today are hard to touch.

“There’s a sophisticated simplicity,” outlines producer and film maker John Blanch, whose work regularly appears on medici.tv, and who remembers being floored, watching the Beethoven films as a young musician, by how they were more innovative than most of what he was seeing produced over 20 years later. “It’s not about a lot of cuts either” he points out. “It’s aesthetically beautiful, but the cuts happen sometimes extremely slowly, not in fast succession. There aren’t even hundreds of different viewpoints, but just some that the audience wouldn’t have anticipated or be used to.”

It had been on a 1959 tour of Japan with the Vienna Philharmonic that the idea of filmed concerts had first entered Karajan’s radar. Their performances were live-broadcast on TV, and when these were the days when there were only a couple of television channels, everywhere they went, everyone knew them. So he saw the power of the medium, and upon returning to Berlin organised a film location, with all the cameras, lights, production crew and musicians, and spent a few days experimenting with all the different ways one could film an orchestra performance.

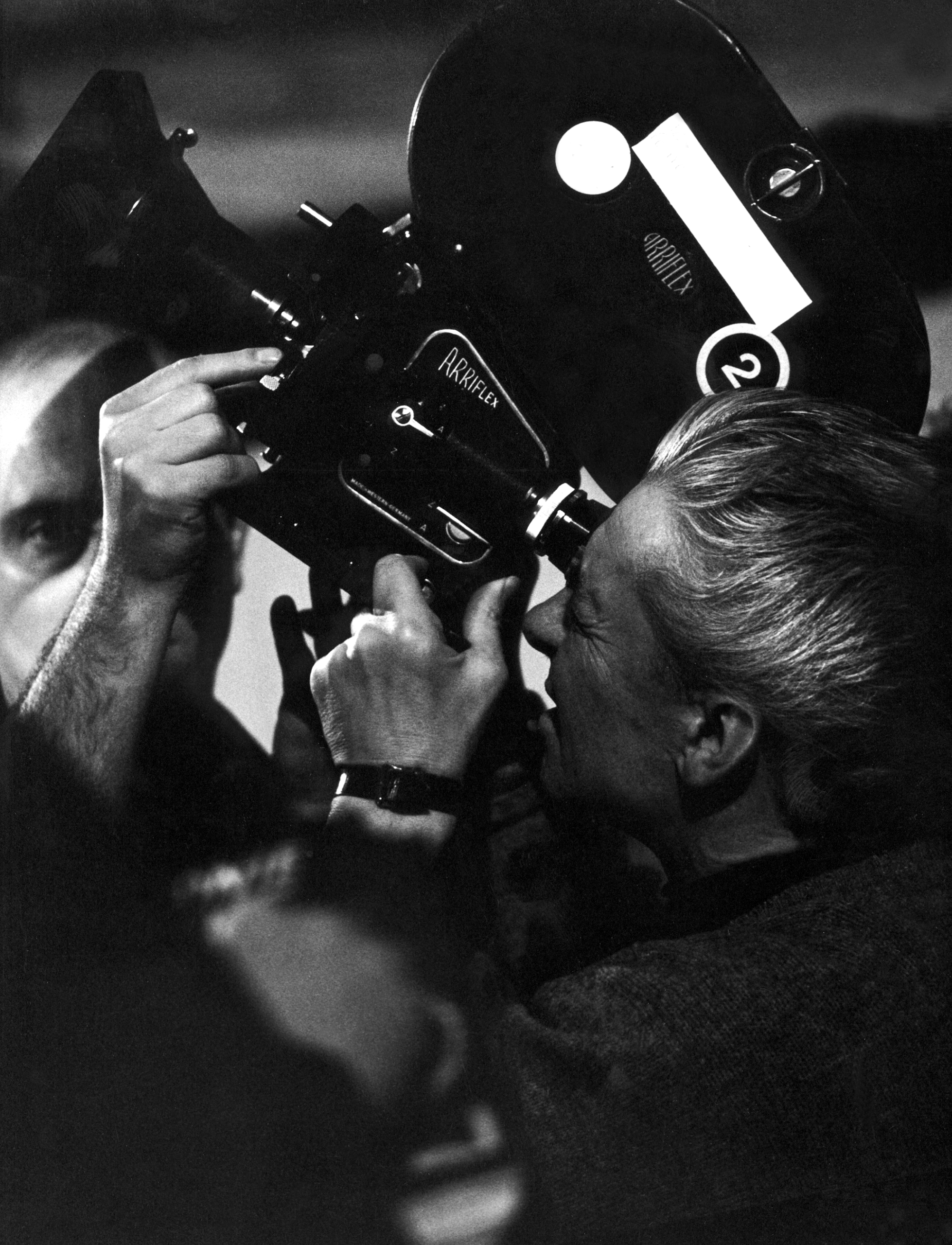

“What he realised” recounts Röder, “was that the options with TV are extremely limited, because when you film the orchestra from one angle, the positioning of the lights and cameras means you can only film it from one side. Also, that when you watch a filmed music, your visual receptors are more dominant than the auditory ones”. He therefore decided to produce music films as for a Hollywood films, in 35 mm, every scene even lit in a specific way – and painstakingly choreographed so as for visuals to constantly guide the attention towards the music.

I lived 10 years too early and will therefore miss so many of the technological advancements. – Herbert von Karajan

“Karajan was very happy that he lived in a time where mass media allowed him to bring to everyone something that was formerly only for the few,” emphasises Röder, “even if at the very end of his life he famously said, ‘I lived 10 years too early and will therefore miss so many of the technological advancements.'”

Nowhere was Karajan’s meticulousness more at play, or indeed his sense of time running out for him, than when he embarked on that grand, repertoire library project, filmed and produced by the film company he himself had set up and ran, Telemondial. Speaking to Gramophone’s Richard Osborne in April 1988 when Osborne visited his home in Anif (whose outbuildings housed film editing suites), Karajan observed, “I was under pressure for the first two years when we started the thing, since I didn’t know whether I would be living to the end.” Still, he said, while there had been setbacks (he meant technical ones, although famously the Chinese authorities had also refused him permission to film Turandot on location in the Forbidden City), the techniques had now been mastered, guidelines set, and his faith in his team was solid. The process he then described to Osborne did then sound formidable. First, the to-be-filmed work’s musical “backbone” was identified. This would then inform the planning of close-up filming (“Karajan detests music filmed in vague middle or long shot”), matching images of the conductor to the instruments in such a way as to lead the ear and eye. Two days’ preparation using a student orchestra would then precede shooting with either the Berlin or Vienna orchestra, using three camera positions, each equipped with five cameras.

A legacy written in light and sound

One further observation Osborne made on that visit was that, while such a project could have been seen as one massive ego-trip, the impression he had was in fact of a musician simply following the same musical principles that had informed his entire career. Which, almost 40 years later, Röder agrees with. “That’s another aspect of von Karajan image, right?” he smiles. “This sort of egomaniac who only wanted to see himself. When actually, when he talks about music, what he’s always trying to get at is the composer’s intention”.

Indeed the other way in which Karajan harnessed technology, says Röder, was in creating the best possible performance per se. “He would hire an assistant to go through his own and other people’s records, and the composers’ original scores, to get the tempo markings correct” Röder outlines. Also though, Karajan knew that what worked live may not work in a studio. “The Karajan Institute collaborated with musicologists a couple of years ago to analyse his studio-recorded performances versus his live recordings” relates Röder, “and they are quite different in terms of tempo.”

Karajan also worked to smooth filmed music’s commercial path. The annual four-day IMZ Avant Première international trade show for performing arts on screen was founded in 1961 upon his suggestion. “He said, ‘Now that we’re producing all of these films, we have to have a marketplace for them'” says Röder. In fact Karajan’s business acumen – he was a supreme salesperson who sold more records than the Beatles – attracted critics accusing him of selling out to the mass market. Yet as projects such as his Schoenberg Variations for Orchestra recording showed – a huge commercial success, despite him having to push Deutsche Grammophon hard for permission to record it – he’s better described as an example of someone who could be commercial and not sell out.

Excerpts from Schoenberg’s Variations for Orchestra

As for today’s digital streaming, does Röder think Karajan anticipated that far? “He was 100 percent convinced that in the future there would be satellites live-broadcasting the orchestra, life-size, into everyone’s home,” Röder responds. “It’s not quite the same, but it’s similar”.

What Röder is convinced of, though, is that if Karajan were still with us, he’d be keeping himself very busy with all the technology he mourned he’d never touch. “The possibilities of AI and virtual reality would have blown his mind. He would have probably built a festival hall with projectors and immersive sound. He’d be equally engaged in decentralised music distribution, and making sure that the money flows”.

While Karajan didn’t get to do all that, he would surely be happy that with the guiding principles of his films projecting out as clearly as they do, they are now inspiring the current generation of musical film makers. “When I think about them,” muses Blanch, “it’s not who the filmmaker or production company were which first comes into my head, but the music itself. How it is sculpted. And it’s this that motivates me daily in what is a difficult profession. The music is the centre of what you’re doing. Not the work of filming. This is how it should always be”.