One of the 20th century’s most dramatic symphonies owes its existence to poor eyesight.

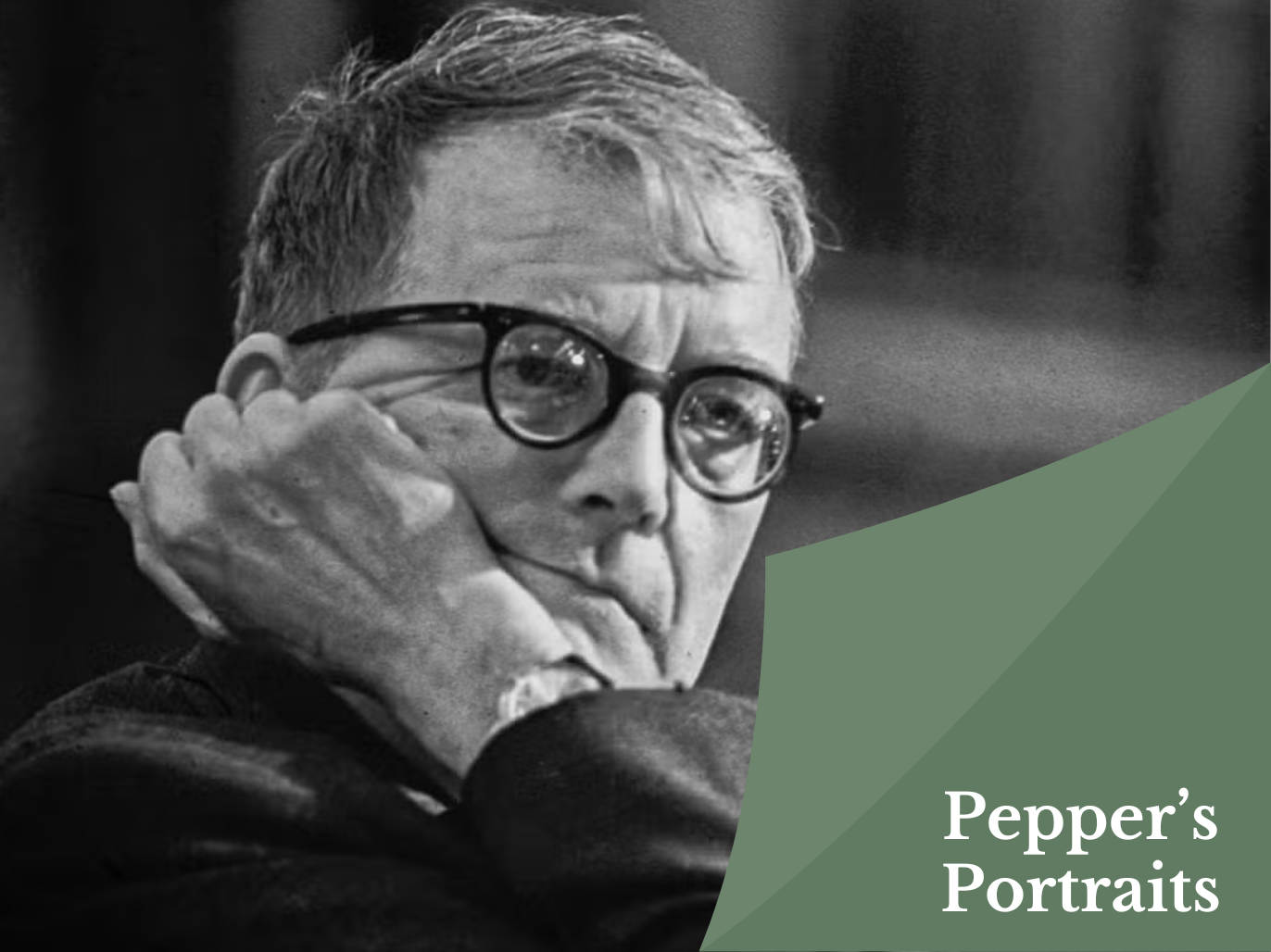

Myopia had prevented Dmitri Shostakovich from enlisting in the Red Army and the Civil Guard come World War Two. Instead, he joined a firefighting unit that drew on professors and students from the Leningrad Conservatory; he would climb to the fifth-floor roof of his apartment block to monitor Nazi incendiary bombs around the school in which he worked. Such was the propaganda power of this image, Shostakovich was featured on the cover of Time Magazine in July 1942 (with the composer wearing a fireman’s helmet… and oven gloves!). A classical musician had become a warfighting icon.

Fire duties occupied him by night; Shostakovich the composer remained in demand by day. He churned out twenty-seven arrangements and two choral pieces for morale-boosting concerts on the frontline, before turning his hand to a Seventh Symphony: