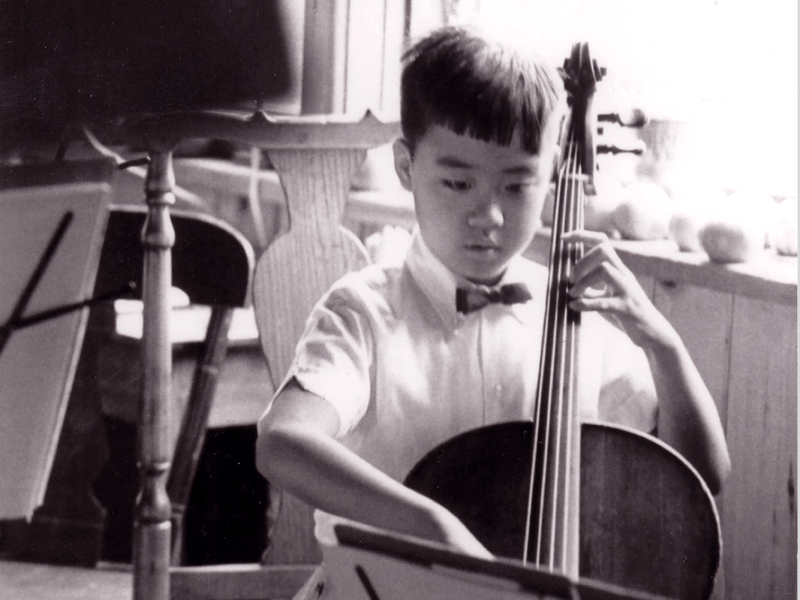

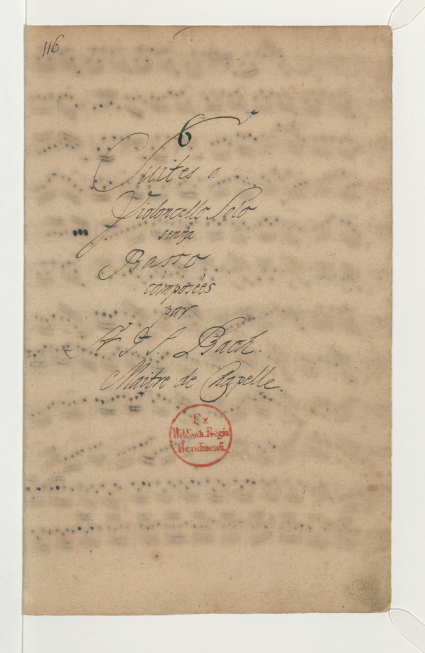

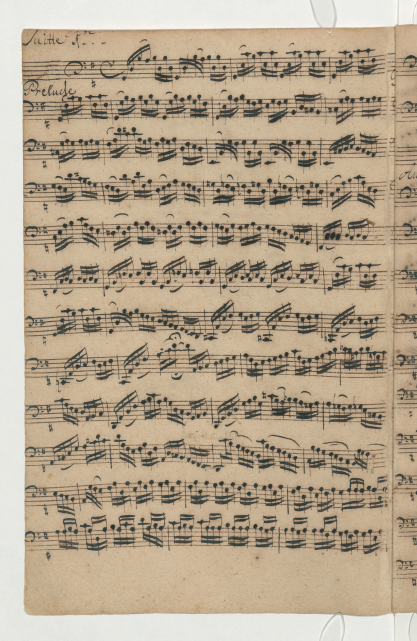

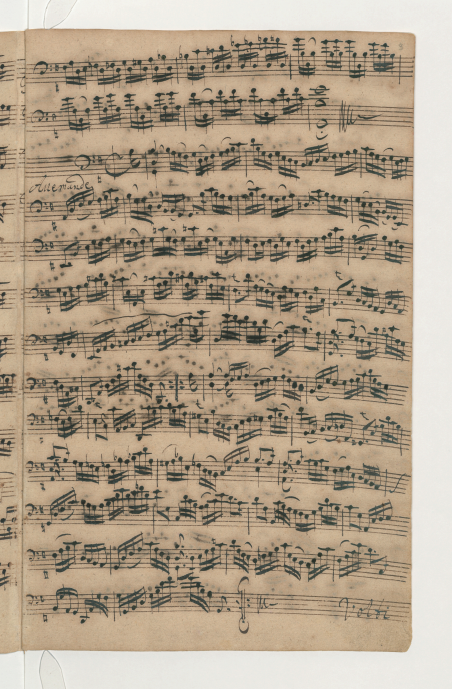

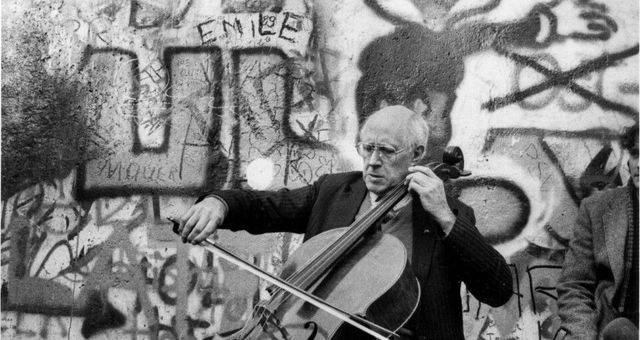

Even as their creator took his rightful place as one of the preeminent composers of all time, this music languished in obscurity. More than two centuries passed before this collection of six suites was first recorded. Miraculously, it was a young boy in a Barcelona thrift shop who resurrected the music that would come to be called the Mount Everest of the cello repertoire. Since then, this collection has been performed the world over and recorded by hundreds of soloists. These are Johann Sebastian Bach’s Six Suites for Unaccompanied Cello.

What is it about this music that continues to inspire and challenge the greatest cellists? How does a 300-year-old composition for only one instrument captivate the hearts, minds, and ears of those who listen? Over the course of a two-hour performance, Bach’s music runs the emotional gamut from ecstasy to tragedy. Though the Suites demand virtuosity, they provide ample space for cellists to bring freshness to every performance. Explore what has been called the “essence of music” itself.