To watch film of the Russian ballet dancer Maya Plisetskaya on stage is to witness a paradox in motion. The Bolshoi prima ballerina assoluta, the centenary of whose birth falls on November 20, embodied an art form of imperial discipline and ethereal grace, yet her dancing was forged in the crucible of Soviet terror and personal tragedy. Her long, defiant career – spanning the darkest days of Stalinism and the dawn glow of glasnost – serves as a remarkable example of how artistic genius can not only survive a repressive state but subtly challenge its very foundations (one is tempted to invoke the name of Dmitri Shostakovich as a comparable spirit from a generation earlier). Central to this story is Plisetskaya’s remarkable 50-year partnership with the composer Rodion Shchedrin, a union that was both a sanctuary and a creative laboratory. It was through the music of Shchedrin – and, specifically, his sizzling reworking of the music of Bizet’s Carmen – that I was led to my first, and unforgettable, encounter with Plisetskaya’s artistry.

View author's page

Reading time estimated : 8 min

Maya Plisetskaya’s biography reads like a Russian novel, its early chapters steeped in deep pain. Born in Moscow in 1925 to a Lithuanian-Jewish family – her father an engineer, her mother a silent-film actress – her childhood was shattered by the Great Purge. In 1937, her father was summarily executed (despite his deep-seated, and officially acknowledged, Communist beliefs). Her mother was arrested the following year and eventually sent to the Gulag, leaving Maya and her younger brother in the care of an aunt, the ballerina Sulamith Messerer. This early encounter with profound loss and the capricious cruelty of the state instilled in Plisetskaya a resilience that would later manifest itself as an audacious, almost rebellious, authority on stage. The Bolshoi Ballet School, which she entered at the age of nine, became her refuge and her instrument. It was a system that demanded absolute physical submission, a price she was willing to pay for the autonomy that supreme technical mastery could grant.

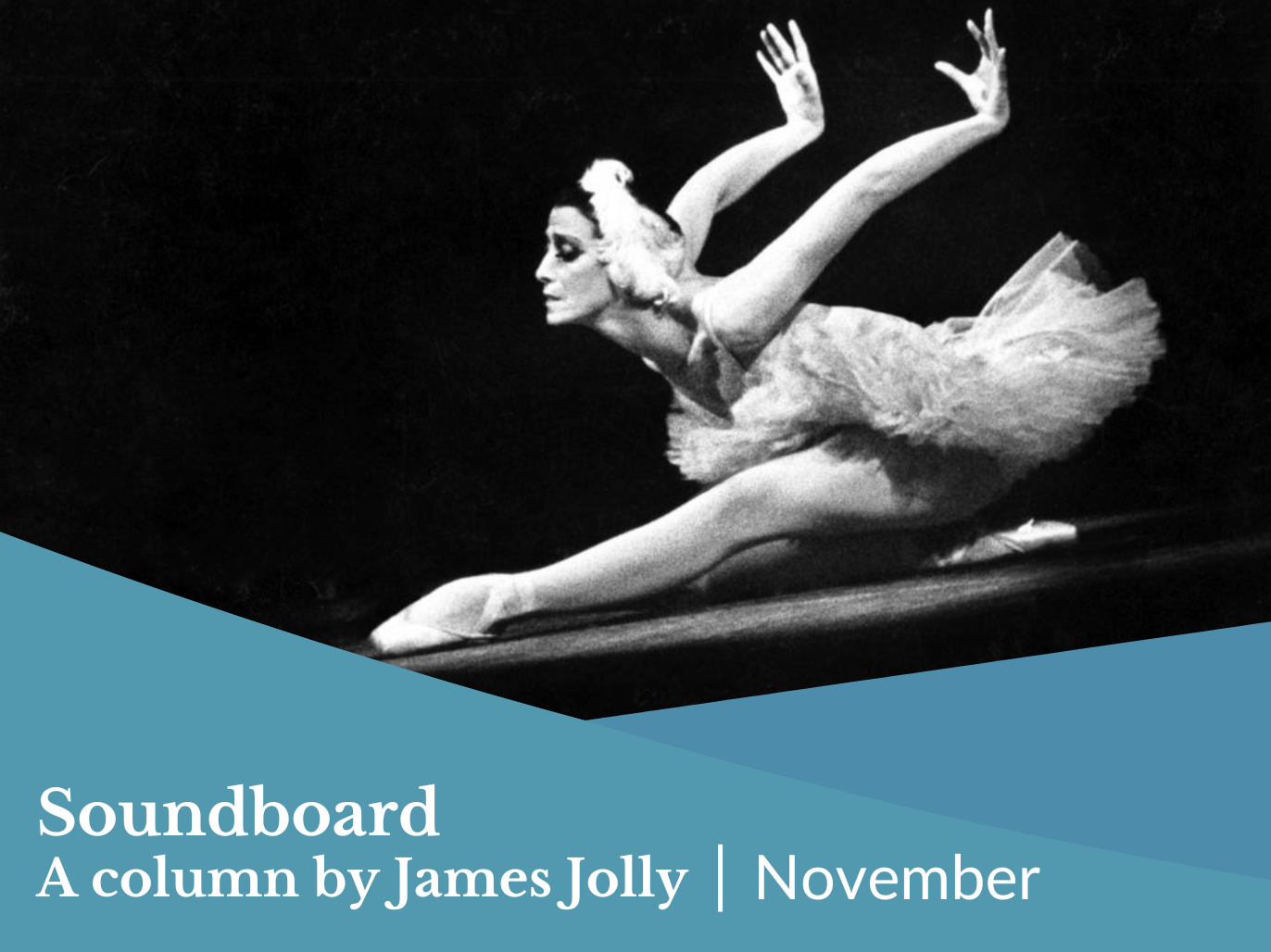

Her ascent through the ranks of the Bolshoi was meteoric, yet perpetually fraught, largely due to systemic antisemitism. The same state that had destroyed her family now celebrated her as a cultural trophy. She became a prima ballerina in 1945, but for years she was denied permission to tour abroad, the authorities fearing she would defect (as Rudolf Nureyev, Natalia Makarova and Mikhail Baryshnikov of a generation later all did). Her artistry was a potent blend of breathtaking technique and raw, dramatic power. She was not a fragile sylph; she was a force of nature. Her famous arms, likened to ocean waves, could convey tragic fragility one moment and imperious command the next. This unique physicality defined her landmark roles.

As Odette-Odile in Swan Lake, she transcended the dual role’s technical challenges to deliver a devastating psychological study. Her Odette was not merely a cursed maiden but a creature of profound, intelligent sorrow. Her Odile was not just a seductress but a manifestation of chilling, triumphant evil. In ‘The Dying Swan’ (a solo she made utterly her own), she transformed a potential piece of sentimental kitsch into a three-minute meditation on mortality, every flutter and shudder of her arms and torso feeling entirely spontaneous yet perfectly controlled. One wonders, watching it, how much of her horrifyingly close-up childhood experience of death infused this concise creation.

It was her collaboration with Rodion Shchedrin that allowed her to break free from the constraints of the 19th-century repertoire and forge a new, distinctly modern identity. They met in 1955 when he was a young firebrand composer and she the established star. They married in 1958, forming a bond that would last until her death in 2015. Their relationship was a private bulwark against the intrusive state, but artistically, it was a dynamic and productive collision.

Shchedrin, a composer of wit, innovation and formidable technique, became her most important artistic co-conspirator. He understood her physicality and dramatic instincts intimately, composing music that stretched her capabilities and matched her scale. Their first major collaboration, Carmen Suite (1967), was a succès de scandale. Shchedrin’s arrangement for strings and percussion stripped Bizet’s grand opera down to its passionate, percussive essence. Choreographed by Alberto Alonso to showcase Plisetskaya, the ballet was shockingly sensual and direct for a Soviet stage. Plisetskaya’s Carmen was a revelation – fiercely independent, erotic and defiant, a character who seemed to dance not for any figure of authority, but entirely for herself. The Soviet cultural bureaucracy was horrified, delaying its premiere and limiting its performances. Yet it became an instant classic.

This pattern repeated itself. Shchedrin wrote Anna Karenina (1972) for her, a score full of dark, churning Romanticism, yet re-invented in a modern, often visceral, language, that provided the perfect soundscape for her portrayal of Tolstoy’s tragic heroine. She did not just dance Anna; she was Anna – a woman of immense passion and intelligence, crushed by the hypocritical conventions of her society. It was a role that resonated deeply with an artist who understood the price of non-conformity.

Perhaps their most ambitious collaboration was The Seagull (1980), after Anton Chekhov. Shchedrin’s score is complex, atmospheric and often of scarifying intensity, avoiding literal illustration in favour of a nuanced psychological portrait. Plisetskaya, who also made the choreography, embodied the tragic actress Irina Arkadina with a depth that only an artist of her experience and emotional intelligence could muster. These works, created specifically for and with her, ensured that her artistic evolution did not cease with middle age but deepened, finding new expressive power in dramatic complexity.

The Plisetskaya-Shchedrin partnership was a fascinating microcosm of the artist’s relationship with the Soviet state. They were insiders, celebrated and decorated (both were Lenin Prize winners). Yet they consistently operated at the very boundaries of what was permissible, using their privileged status as a shield to push back aesthetic boundaries. They were not dissidents – the Soviet Premier, Nikita Khrushchev, greeting her on her return from a US tour, thanked her: ‘Good girl, coming back. Not making me look like a fool. You didn’t let me down.’ Instead, Plisetskaya and Shchedrin were subversives from within the system, proving that even state-sanctioned art could carry a potent, independent spirit.

In her later years, as the Soviet Union crumbled, Plisetskaya’s status transformed into that of a global elder stateswoman of dance. The list of her friendships is testament to her magnetism (Leonard Bernstein, Arthur Rubinstein, Marc Chagall, Jacqueline Kennedy, Ingrid Bergman, Shirley Maclaine, Warren Beatty, Natalie Wood and Robert F. Kennedy all counted themselves as part of her circle). She continued to perform astonishingly late into life, her artistry shifting from pyrotechnics to profound characterisation. Her partnership with Shchedrin remained the bedrock of her existence, a lifelong dialogue between movement and music.

A century after her birth, Maya Plisetskaya’s legacy is multifaceted. She is remembered for her sublime technique, the unforgettable roles and the sheer longevity of her stage presence. But more importantly, she is remembered for her unbreakable spirit. She was an artist who used the often rigid, formalised language of classical ballet to express an utterly individual and resilient soul. Her life and work stand as a testament to the idea that even in the most oppressive circumstances, the human spirit, channelled through supreme discipline and aided by a true creative partnership, can achieve a form of glorious, unstoppable freedom.