If ever there were an over-used superlative when it comes to, well, anything, then it’s “iconic”. Yet if ever there were a work of art to which that word still genuinely fits like a glove, then it’s Glenn Gould’s various readings of JS Bach’s Goldberg Variations. Whether we’re talking the exuberant 1955 mono studio recording which launched his international career at the age of 22, or his significantly slower studio revisit from 1981, or the film he shot right before his 1982 death with Bruno Monsaingeon, Glenn Gould Plays the Goldberg Variations, Gould’s readings stand tall and entirely apart in the recorded-Bach firmament, with it feeling as impossible as it is nonsensical to even try to compare them with the work of other pianists. There’s his dazzlingly defined and rhythmically controlled articulation, holding its perfection across even staggeringly fast tempi. Also the sheer range, imagination and (some would say) eccentricity of his phrasing, and his soft vocalising over the top. Then the surrounding legend of his obsessive control over everything from tempi decisions to his precisely-measured low seating position—aided by his famous custom-made chair. But best of all, the sense of joy-filled fresh new-mintedness radiating out.

View author's page

Reading time estimated : 10 min

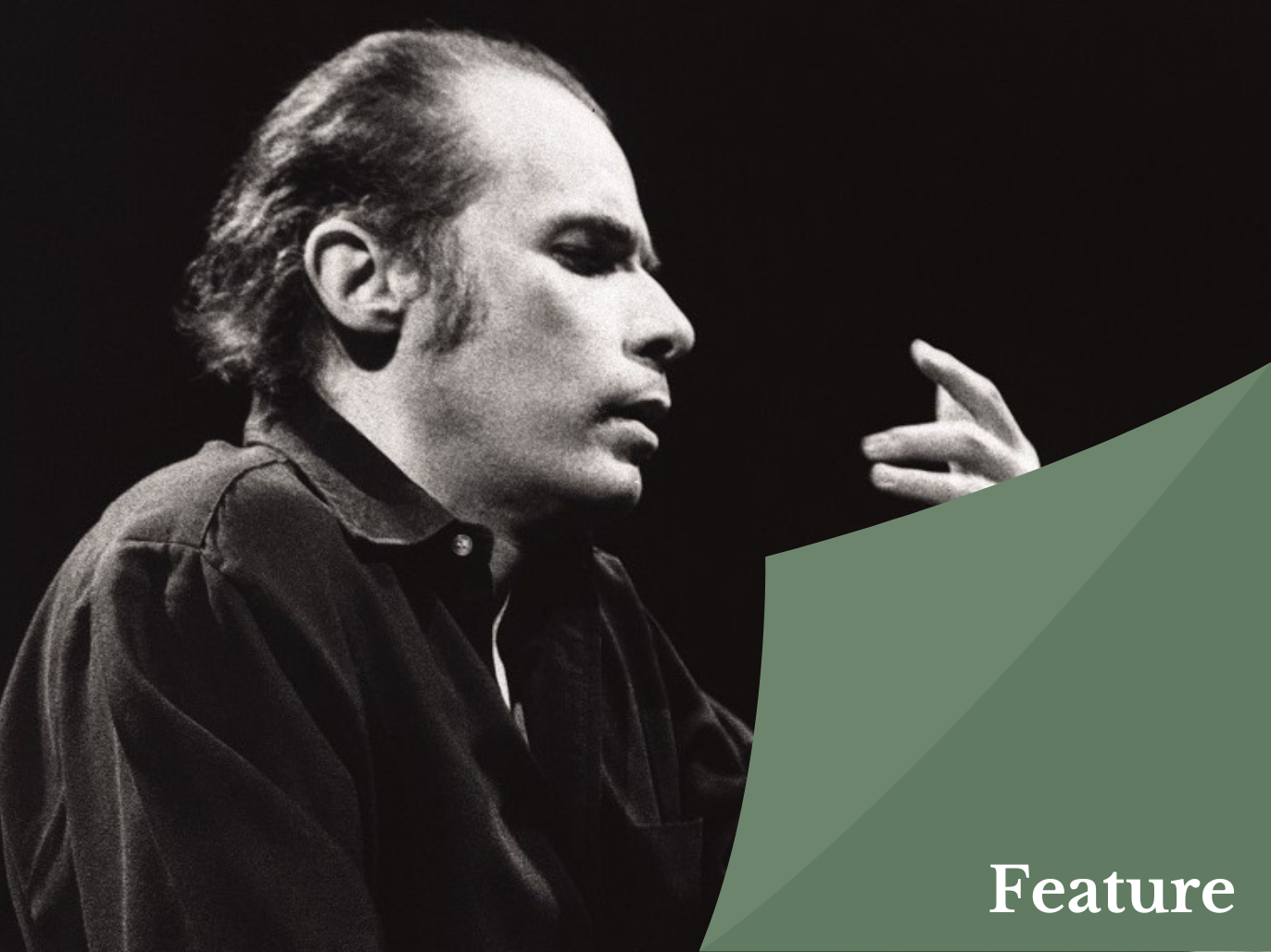

Glenn Gould performs Johann Sebastian Bach’s Goldberg Variations, BWV 988 – Aria, in Bruno Monsaingeon’s 1981 film.

Mathematical Precision and Artistic Instinct

Essentially, it’s no wonder that Gould’s Goldbergs have touched so many people over the decades, and equally no wonder that one such person is Bruno Monsaingeon, given their close working relationship’s roots stretched all the way back to their first meeting in 1972. “Even now,” muses the legendary filmmaker, “40 years after our film and his death, whenever I start editing I always have a communication with him. To me his death was physical, but certainly not spiritual.”

By way of a reminder, beyond high beauty, emotional profundity, and moments of extreme virtuosity, the Goldberg Variations stand out for a phenomenally mathematically balanced overall architecture: an aria and its da capo repeat, separated by 30 variations, every third variation cast as a canon whose separating interval is a tone wider than the previous canon, with the whole written in G major, excepting nos 15, 21 and 25 in G minor. In other words, a perfect project for a deep-thinking intellectual and virtuoso such as Gould; and thinking back to their joint preparations for the 1982 film, Monsaingeon reflects, “I think that with his very last recordings he had reached a state of mind which was one of autumnal repose. A kind of meditation on the subject of music. In the final months before filming began, he would call me every night, and would sing one version after another. He was talking about the kind of mathematical precision that he would like to bring. He had this formidable line running from the first G to the last, and it had to be mathematically proportioned in terms of tempo—his idea about the notion of tempi was absolutely rigorous, and also the duration of the silence between variations. All these things were completely thought out before we started shooting, in a way that would not change. Yet at the same time, when we came to record, each take was different—just not in tempo. He had such imagination that he could change the articulation to make 20 valid versions of the same variation. It was incredibly haunting and inspiring.”

Playing as a Performer, Thinking as an Actor

One other aspect which shines from that film, and in Monsaingeon’s memory, is how, despite Gould’s controversial 1965 decision to retire from live concerts in order to dedicate himself to recorded performance, he thought deeply about the communication of music. One striking moment in Monsaingeon’s film sees the two of them finish a take, and Gould immediately asks whether the camera had been trained on his legs. Told not, he comments that this was a shame because he had deliberately crossed them in order to emphasise the music’s carefree aspect. “So he had very much the sense of playing both as a performer, and as an actor,” sums up Monsaingeon. “People thought he was selfish and a recluse, and he was a recluse, but certainly not selfish. On the contrary, he really wanted to have communication, and was very concerned about the people who could be touched by what he’d done. It just didn’t have to be physical.”

Monsaingeon describes Gould’s concentration as producing a studio atmosphere that, at times, could be incredibly intense—meaning that some variations, such as the 15th with its dramatic first appearance of G minor, were done in just one take. Yet as that leg-crossing moment illustrates, the atmosphere could also be very light, helped in part by there wasn’t the stress of multiple takes simply to get a technical aspect right. “In terms of pure performance, he didn’t need very many takes,” points out Monsaingeon. “But also Glenn knew that editing was not about correcting anything, but about constructing. And the atmosphere could be joyful. When Glenn knew that we had captured the thing he wanted, he just beamed.”

Gould’s Legacy: Redefining the Untouchable

So what, then, was Gould’s late-life view on his 1955 version, given that its 13 minutes shorter duration was as much down to its slower speeds as to its featuring more of the music’s repeats? “He thought it was too pianistic,” states Monsaingeon. “Too contaminated by the instrument, with too much focus on sheer virtuosity and instrumental effects. He thought it was alright, but immature, and that now he wanted to make something for the final, for the future, after which he would never play it again.”

In the event, all the versions have become his legacy—one that, beyond the pleasure it has brought to generations of listeners, has been hugely important for pianists. Take Beatrice Rana, who recorded her own critically acclaimed Goldbergs aged just 23, and who describes the 1955 recording in particular as being actually part of her DNA, it having had such an impact on her when she first listened to it, aged ten or eleven.

“My family had a Glenn Gould CD Collection that had been released by an Italian newspaper,” she begins. “The third disc was the 1955 Goldbergs recording, and I remember the moment I first pressed play as though it were yesterday, I was so shocked by what I heard. At the time, I was a piano student in the conservatory, and playing Bach was all about NO. ‘No, you don’t do this. No, you cannot play like that.’ Whereas this was like a huge, giant YES, and finally, Bach made so much sense to me.”

Indeed it wasn’t even just Bach who suddenly made so much more sense to her. “Composers such as Bach, Beethoven or Mozart are often seen in the academic work as gods in a temple” she continues. “Kind of untouchable. Yet when you try to find your way as an interpreter, you have to touch the music. You have to understand. So that first listening experience was mind-opening also in a wider sense for myself as a pianist, because I thought, ‘Well, I never heard anything like that, but it’s possible, it’s doable, and it is actually very nice. So why shouldn’t I do that?”

Asked which moments of that 1955 reading especially struck her, Rana immediately cites Variation 13—the first slow variation, and now one of her own favourites to play. “I remember that I loved the invention of his playing” she outlines, “and also, unlike with so many recordings, the flow never stops. The variation just emerges as a natural evolution of Variation 12 and a prequel of Variation 14.”

The almost harpsichord-like definition of Gould’s articulation is another draw. “What I love about the harpsichord is its rhythmical aspect and ornamentation culture,” she describes. “In the piano we always develop the melodic aspect, and somehow with Gould it’s like you can also bite the rhythm.”

Engaging Modern Audiences

Whichever of Gould’s versions floats your personal boat, the other remarkable thing about Gould was that, in all likelihood, his greatest desire would be simply that you did have a personal opinion. Asked what Gould’s ultimate wish might have been for that final 1982 film, Monsaingeon suggests, “Ideally, he would have liked to have been able to give the listeners all the rushes of all his differently articulated takes, in order that they could make their own final version—which might differ from one day to the next—and even that they might weave in versions by other pianists, if for instance they preferred Peter Serkin’s Variation 11 to his. Glenn was convinced that listeners should be participants, using their own competence and desire, to make it their own performance. He thought that the disappearance of amateur musicians was something terrible. He had absolutely no pretension as to authorship, even though he was the most autocratic of them all in terms of his wanting absolute perfection.”

Which brings us back to the adventurous freshness of mindset which his recordings exude—and which, for Rana, is ultimately at the root of their enduring power. “Gould’s Goldbergs are so iconic and immortal because of their connection to the present,” she emphasises. “They demonstrate that classical music doesn’t belong in a temple, as a relic of the past, but that when played and listened to, it belongs to the present. There are certain old recordings that, as you listen, you think about how much more we now know about that repertoire’s performance practice. They’re a reflection of the time in which they’re recorded. Yet even with how much more we know these days about Bach performance, Gould’s Goldbergs still feel as though they were recorded yesterday. So for me they’re not simply a recording of the Goldberg Variations. They’re a statement about how music should be perceived by everyone, every day. That classical music is alive.”

Glenn Gould performs Johann Sebastian Bach’s Variation 21.