Amongst the strife and confusion of the 30s in Europe, Austrian composer Alban Berg brought to life what would become some of the most poignant works of the 20th century. After the success of his first opera Wozzeck which keenly mimicked the cruelty of the recently abandoned First World War, Berg started work on Lulu. Sadly unfinished by his own hands, Lulu was a work of female resilience so revolutionary that it attracted the ire of the Nazi regime.

View author's page

Reading time estimated : 5 min

“It is a sign of the times that this work can only be given a performance in Zurich,” wrote a Swiss paper in June 1937. The opera in question was Alban Berg’s opera Lulu, which received its premiere at the opera house on June 2. Berg himself was Viennese, but the chance of a performance in Austria, or Germany for that matter, was minimal, on account of the artistic tastes of the ruling Nazi party.

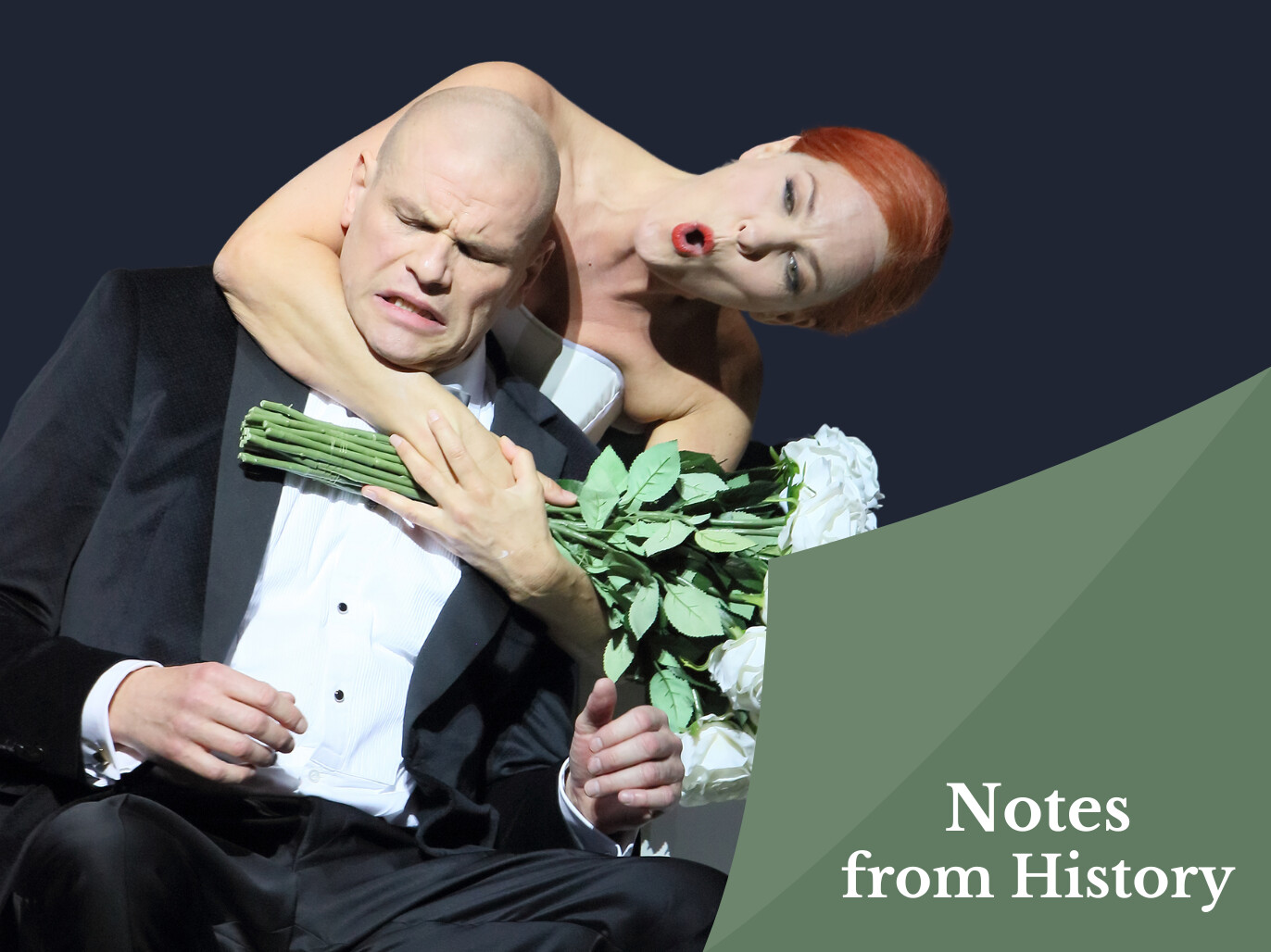

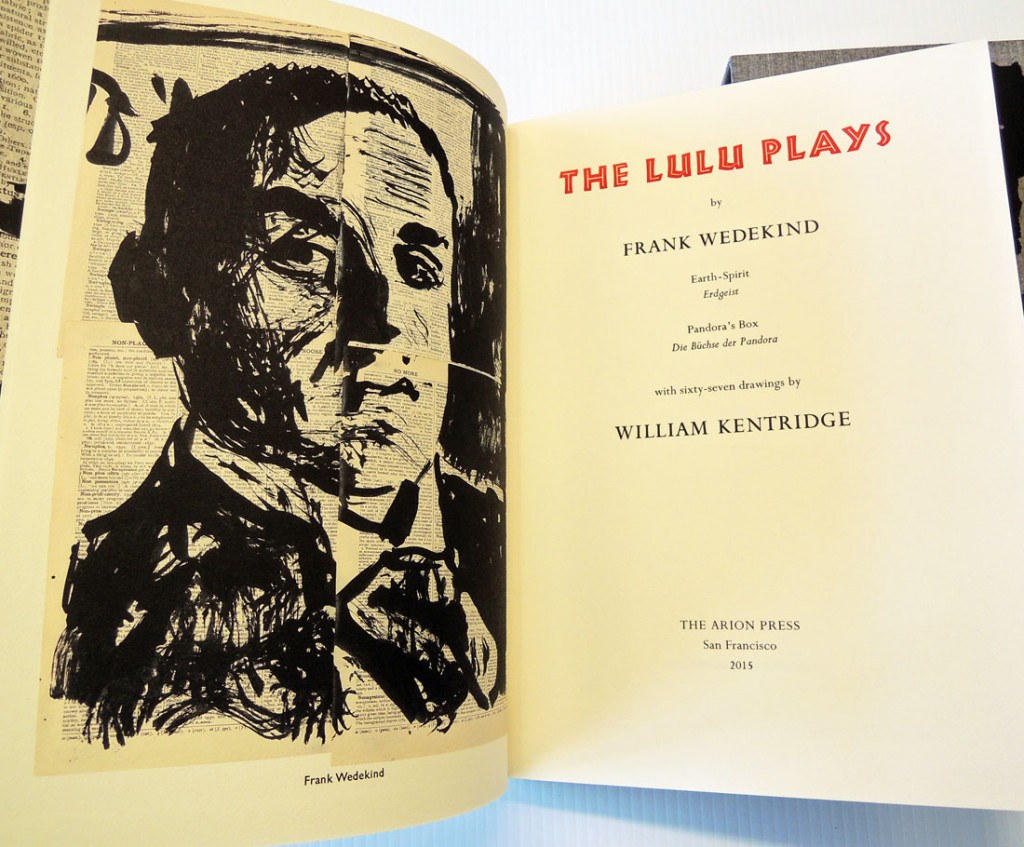

Berg’s music was “degenerate” enough on its own: the Nazis were opposed to the serial style of Berg and his teacher Arnold Schoenberg. But there was also the subject matter of the opera to contend with. Berg’s Lulu is based on two plays by Frank Wedekind that chart the slow descent of Lulu, a femme fatale who takes a series of lovers, all of whom die, before she herself is killed (by Jack the Ripper) while working as a prostitute. This was not the sort of narrative Hitler and his party were wont to allow in the opera house.

Berg himself had observed how his work was doing better abroad than at home, in a letter of November 1935. Having noted upcoming performances of his Lulu Suite in Zurich, Stockholm, Copenhagen and Philadelphia, he wrote: “there will be Austrian music everywhere but in Austria itself. Amusing, isn’t it?!”

He would doubtless have become less amused had he lived on: tragically, he died just over a month after writing that letter, on Christmas Eve 1935, from an infection caused by an insect bite. Also unamusingly, he had not yet completed his opera: although he had drafted the whole thing, he had only orchestrated the first 268 bars of the concluding Act 3. It was almost complete, in other words—and closer to completion than some other unfinished works, like Bruckner’s Ninth or Puccini’s Turandot—yet still nowhere near ready to present as a finished work on stage.

The Zurich premiere, then, was not of the whole thing. The first two acts, both complete, were fully staged, but, in place of the third act, the director came onto the stage and explained the situation, followed by a performance of parts of the Lulu Suite and a mimed performance of the stage action.

The novelist Thomas Mann was guardedly impressed: “Superlative production of the fragmentary and difficult work,” he wrote in his diary. “Wedekind’s icy and overwrought dialogue is softened by the music which is at its loveliest in the interludes.”

Predictably, the Nazi journal Die Musik was less enthusiastic, describing the opera as “a music of prostitutes and pimps, bondsmen and the criminal world. Doubtless very knowing and impressive; a deliberate tearing at the nerves, a brutal whipping of the air… but these are the old shocks of yesteryear.”

Despite the opera’s closeness to completion, it would be 42 years before a completed version would be produced: Pierre Bouelz conducted a completion by the Austrian composer Friedrich Cerha in Paris on February 24, 1979. The composer’s widow Helene had been staunchly opposed to completion, and the project waited until after her death in 1976.

It was undoubtedly worth the wait. The third act is the opera’s most shocking, as the characters meet their brutal ends and Berg’s curiously sensuous music draws to its climax. “The old shocks of yesteryear?” That journalist must have seen some shocking stuff…