Composer Robert Schumann famously described Mozart’s Symphony No. 40 as a work of “weightless, Hellenic charm.” This nineteenth-century reception resonates with Mozart’s image in popular culture as a prolific creator of light Classical music. Symphony No. 40 adheres to the ideals of the Classical period. It employs traditional orchestration in a standard four-movement structure. Musical ideas are balanced and gracefully phrased. So why did modern musicologist Charles Rosen call this same symphony “a work of passion, violence, and grief”?

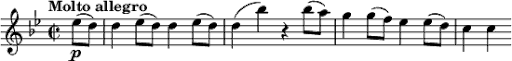

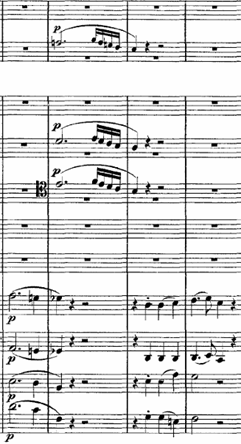

Written in 1788 at a time of personal and professional hardship, Symphony No. 40 is one of only two symphonies that the composer wrote in a minor key. From his poignant String Quintet No. 4 to Pamina’s aria “Ach, ich fühl’s” in The Magic Flute, Mozart’s works in G Minor carry a strong sense of angst and tragedy. The harmonic dissonance and restless tempo markings infuse the work with dramatic tension, showing the influence of the artistic Sturm und Drang movement that prioritized emotion over rationalism. Mozart’s Symphony No. 40 is a work of profound emotional depth, with musical themes that are formally rooted in the Classical tradition but characterized by Romantic expression.