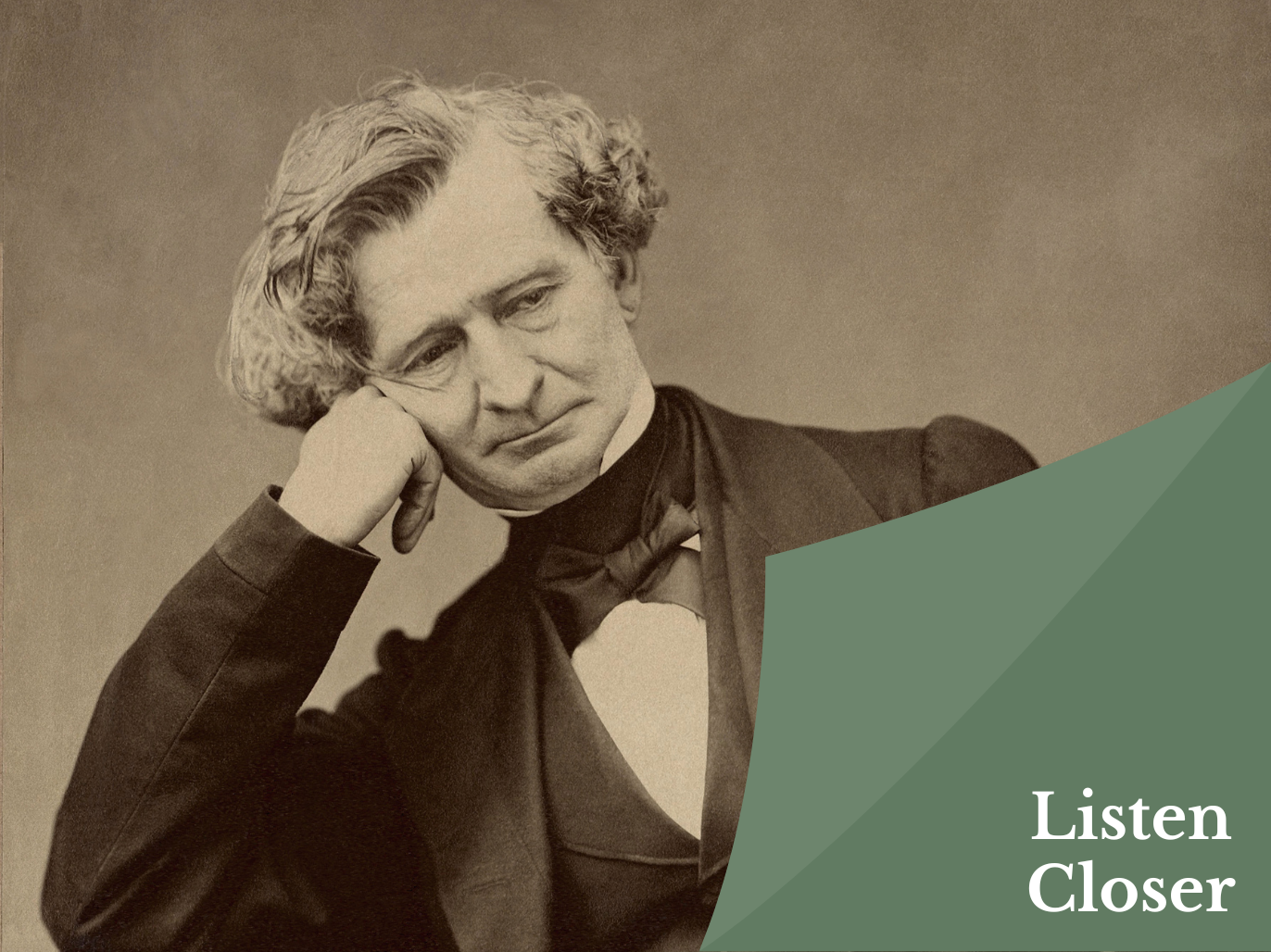

“A young musician of morbid sensitivity and ardent imagination poisons himself with opium in a moment of despair caused by frustrated love […] His beloved becomes for him a melody and like an idée fixe which he meets and hears everywhere,” wrote Hector Berlioz in the original programme notes of his Symphonie Fantastique in 1830. A striking Romantic vision emerges in an original form. Classical symphonies favored the abstract, prioritizing elegant phrasing and structural clarity to convey their expressive power. Berlioz’s imagination flowed beyond this framework. Written for over 90 instruments, the composition extends the usual 4 movements to 5. A melancholic dream transforms into a ball, a scene in the fields, opium hallucinations, and a witches’ sabbath. Berlioz became a pioneer of programmatic music, creating an instrumental drama that traced a turbulent musical journey through the recurring presence of an idée fixe.

View author's page

Reading time estimated : 6 min

The evocative entrance

Three years before the premiere of Symphonie Fantastique, the composer watched a production of Shakespeare’s Hamlet in Paris. Not only was Berlioz profoundly impressed by the Bard’s play, but he was instantly infatuated with actress Harriet Smithson, playing the role of Ophelia. He sent passionate love letters and tracked her every move, even renting rooms near her lodgings. Symphonie Fantastique embodies the height of his feelings for Smithson, a vivid musical appeal for her attention. The idée fixe is a musical representation of the beloved—a recurring melodic fragment heard in every movement in a different guise, with variations on harmony, rhythm, tempo, timbre. A precursor to the Leitmotiv later developed by Wagner, the idée fixe haunts the artist at different stages of the composition to an intensifying effect.

The melody first appears around seven minutes into the composition. The legato theme is played by the violins and solo flute in a largely monophonic texture, allowing the melody to ring out clearly across the orchestra. Originating in Berlioz’s earlier cantata Herminie, it starts on the dominant with expanding leaps, before descending in steps to form a motif resembling a sigh—it is like the artist taking a breath to ask a question, but slowly exhaling, suspecting he knows the answer already. After its solo appearance, the idée fixe is accompanied by eighth-note chords in the other strings, conveying a sense of angst and anticipation. It is then repeated, shifted down a fourth to develop the musical idea. Punctuating rests increase the tension, while the tempo marking of allegro agitato e appasionnato assai and consistent syncopation create a distinct sense of unease. Bernstein captures this emotional arc—and how it ascends into a dramatic climax—beautifully in his performance with the Orchestre National de France.

The idée fixe transformed

Out of the depths of reverie, the second movement floats into the scene of a celebratory ball. The artist tries to embrace the event, but the idée fixe returns once more through the lush orchestral texture. This time, it is transformed into a waltz in triple meter. The melody is fleetingly heard after a couple of minutes, but the idea vanishes as quickly as it came. Marked as dolce e tenero (sweet and tender), the idée fixe is now much more elaborate in quick sixteenth-notes that depict the artist’s nerves amongst the festivities.

The greatest contrast in the style and mood of the idée fixe comes at the conclusion of the composition. “Strange noises, cackling, distant cries” set the programmatic scene of the witches’ sabbath. The idée fixe is a caricature of its former self—long gone are the sighing motifs and flickering sixteenth notes. Instead, they are replaced with a distorted version of the melody, played by an E-flat clarinet in a trivial dance rhythm. The artist demonizes his muse as she remains beyond his reach: easier then to transform her into a witch and change her character completely. This is the melody’s final appearance, as the symphony descends into instrumental insanity with a Dies Irae chant and a witches’ round-dance. Yannick Nézet-Séguin is a master of dramatic contrast—watch how he sculpts this fragmented closing statement of the idée fixe against full-scale orchestral passages with the Vienna Philharmonic.

Defying convention and expressing the grandiose vision of the composer in full color, Symphonie Fantastique takes us from dreamlike melancholy to demonic nightmares. The central thread in this musical tapestry is the idée fixe, twisted into different forms to satisfy Berlioz’s vision. Though the theme is drastically altered, the idea of the beloved remains alive and recognizable. But the artist’s fate is as tragic as Ophelia’s—staging his own funeral, driven mad and torn apart by love, unrecognizable to the wandering soul he was at the beginning.