Everybody knows the story of Hansel and Gretel, the hungry children lost in the woods who escape from an evil witch and her gingerbread house. The story is a staple of children’s fairy tale books, and it’s also beloved of opera audiences, thanks to Engelbert Humperdinck’s classic 1893 adaptation—first performed on December 23, and now a Christmastime tradition. But where does this story come from? And how does the opera relate to the rather gruesome original?

View author's page

Reading time estimated : 9 min

Hansel and Gretel first found a wide audience in 1812, when Jacob and Wilhelm Grimm published their first collection of Kinder- und Hausmärchen (Children’s and Household Tales). The Brothers Grimm worked throughout their lives to record and publish traditional German fairy tales, and they frequently revised their 1812 volume, with the final edition appearing in 1857. Needless to say, they didn’t invent these stories themselves—that would very much have missed the point. Instead, they got other people to tell them the tales they knew.

It’s tempting to imagine the intrepid brothers venturing into the dark woods where so many of their stories take place, in search of wizened great-grandmothers in thatched cottages to tell them tales as old as the forest itself. The reality was more prosaic: in fact, a lot of their stories came from the children of middle-class families in the Grimms’ home city of Kassel. One particularly eloquent source was a young woman by the name of Dortchen Wild, who is believed to have told the brothers the “Hansel and Gretel” story—among many others, including “The Elves and the Shoemaker” and “Rumplestiltskin.”

Dortchen and her family lived next door to the Grimms, and she was a friend of the brothers’ younger sister, Lotte. Years later, she married Wilhelm Grimm, whom she had loved from a young age. It may be the Grimm family name that became famous, but without Dortchen and her sisters the Grimms would have a lot less material: the Wild sisters are the unsung heroines of German fairy tales. That said, Dortchen has attracted interest in recent years. Australian writer Kate Forsyth wrote a novel about her in 2013, entitled The Wild Girl.

Though she was still a teenager when the Grimms’ first version of “Hansel and Gretel” was published, Dortchen’s 1812 telling of the story is not quite the same as many later versions: it’s darker. So dark, in fact, that it’s quite a relief that Humperdinck’s adaptation makes it a little lighter. There were also some substantial changes between the different editions of the Grimms’ book, with the 1857 edition making for far easier reading than that of 1812. So here’s a look at how this famous fairy tale has adapted over the years.

The last piece of bread… and fourteen eggs

Hansel and Gretel live in a little cottage in the woods with their father and… a woman. Originally, the Grimms say that she is Hansel and Gretel’s mother, but in later editions she is a stepmother instead. Why the change? Well, perhaps this horrible woman’s actions are little easier to swallow—only a little, though—if she isn’t a blood relation of the children.

The family is desperately poor, and they don’t have enough food. So the mother—or stepmother—suggests leading the children into the forest, giving them both a small piece of bread, and returning home without them. The father objects: “Wild animals would soon come and tear them to pieces,” he observes. But his wife gets her way.

Fans of Jenůfa and Il trovatore might not see the problem with this: it’s perfectly possible to fit infanticide into an opera plot. But those two operas aren’t very… Christmassy. One of the great things about Humperdinck’s masterpiece is how entertaining it is for the entire family. So he and his sister Adelheid Wette, who wrote the libretto, quite sensibly did away with the (step)mother’s murderousness. In the opera, the mother still has a short temper, knocking over a jug of milk in anger when she catches Hansel and Gretel playing. But she also gets a sympathetic solo aria, in which she prays that God give them money. What’s more, in this version, the mother sends the children into the woods to look for strawberries: she doesn’t mean for them to get lost and die.

Even better, just after the children have gone off on their strawberry mission, their father returns home in good spirits. He’s come into some money and has a mountain of food for the family to eat, including fourteen eggs and—“Hooray!”—a quarter-pound of coffee. In the opera, the father is a broom-maker (he’s a mere woodcutter in the Grimms’ versions). And, as the demand for brooms has suddenly skyrocketed for some reason, the future now looks quite rosy for the family.

Apart from that the children have gone into the woods. The father is somewhat more worried about this than the mother, and the two of them rush off to look for them: quite the opposite of what happens in the book.

A visit from the Sandman

In Dortchen’s tale, Hansel and Gretel spend several days in the woods before they stumble across that sinister gingerbread house. On the opera stage, events are hurried along a little, thanks to a few surprise guests. First, the Sandman comes to lull the children to sleep—a character borrowed from another fairy tale altogether. Then the children say their evening prayer, before a group of angels appears, to protect the children during the night. And finally, as the opera’s final act begins, they are awoken by the Dew Fairy.

Why all these extra characters? Well, they’re kind of irresistible, and greatly enhance the opera’s magical atmosphere. They also grant the opera another solo role (the Sandman and Dew Fairy are frequently sung by the same singer), and a delightful opportunity for a “ballet-pantomime” for 14 angels. And as for the Evening Prayer: that, understandably, has become one of the opera’s enduring highlights.

An unsubtle witch

Nibble, nibble, little mouse,

Who is nibbling at my house?

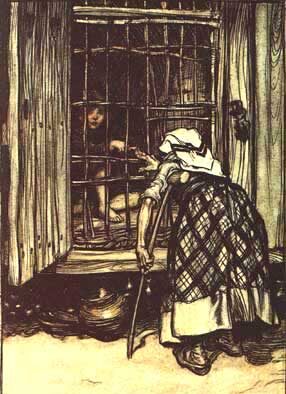

Some things are just too good to change, and the Witch’s sinister little rhyme is one of them. When the children start greedily eating her gingerbread house, both in the book and the opera, this is the rhyme she sings. In fact, when the Witch kidnaps the two children, most of the sources agree more or less on what happens. She imprisons Hansel in order to fatten him up, and enlists the help of Gretel in doing so. And she’s disturbingly upfront about her intentions—“When he is fat I am going to eat him,” she tells Gretel in the Grimm version.

The children catch on pretty quickly in the opera, too, in which the Witch can be sung by a variety of different voices. Originally written for mezzo-soprano, it can also be sung by a tenor The part is also sometimes taken on by the same singer who plays the Mother. And in Johannes Felsenstein’s production from Dessau, the Witch is sung by the children’s Father, playing out a puppet game.

The Witch’s plan, of course, is to eat not just Hansel but Gretel too, by swiftly shutting the oven door once she has climbed in to test the temperature. In the written story, Gretel tricks the Witch all by herself, but in the opera Hansel lends a hand as well.

Happily ever after

According to Dortchen, once the Witch is burned, the two children conduct a swift pillaging of her house, filling their pockets with precious stones and pearls. The 1812 version is a little hazy on how the children find their way home, but by 1857, Dortchen and the Grimms clarify that they enlist the help of a magical white duck that graciously escorts them across a lake. When they get home, their father is overjoyed to see his children, especially as their pockets are filled with jewels. His unpleasant wife has died.

Opera isn’t generally an art form to pass up the opportunity for a bit of glitz, but there’s no jewelry in Humperdinck’s version of the story. Instead, Hansel and Gretel discover an entire cake’s worth of gingerbread children, who return to life the minute the Witch is killed. Then Hansel and Gretel’s parents finally find them—remember, in the operatic version they were actually worried about their children—and the joyous final scene is complete when the Witch emerges from the oven… as a piece of gingerbread. The father zealously explains this as an act of God: in the children’s hour of greatest need, God saves the day with an ironic punishment.

Dortchen and the Grimms’ ending is a happy one, but in a thrillingly medieval sort of way: there is death and theft galore. But the opera clears up all the moral uncertainty through its carefully pitched religious note, as well as by showing the two parents in a far more sympathetic light—and the opera also turns Hansel and Gretel themselves into the saviors of a group of lost children, rather than opportunistic thieves. It all adds up to an opera that’s perfectly suited to the festive season, and for the whole family to enjoy.

But while Humperdinck and Wette’s Hansel und Gretel strikes a very different sort of tone, there are plenty of details from Dortchen’s version that still shine through, from the mother’s angry disposition to the Witch’s creepy nursery rhyme. Her name might not appear on any editions of the story, but we have a lot to thank the young Dortchen Wild for.