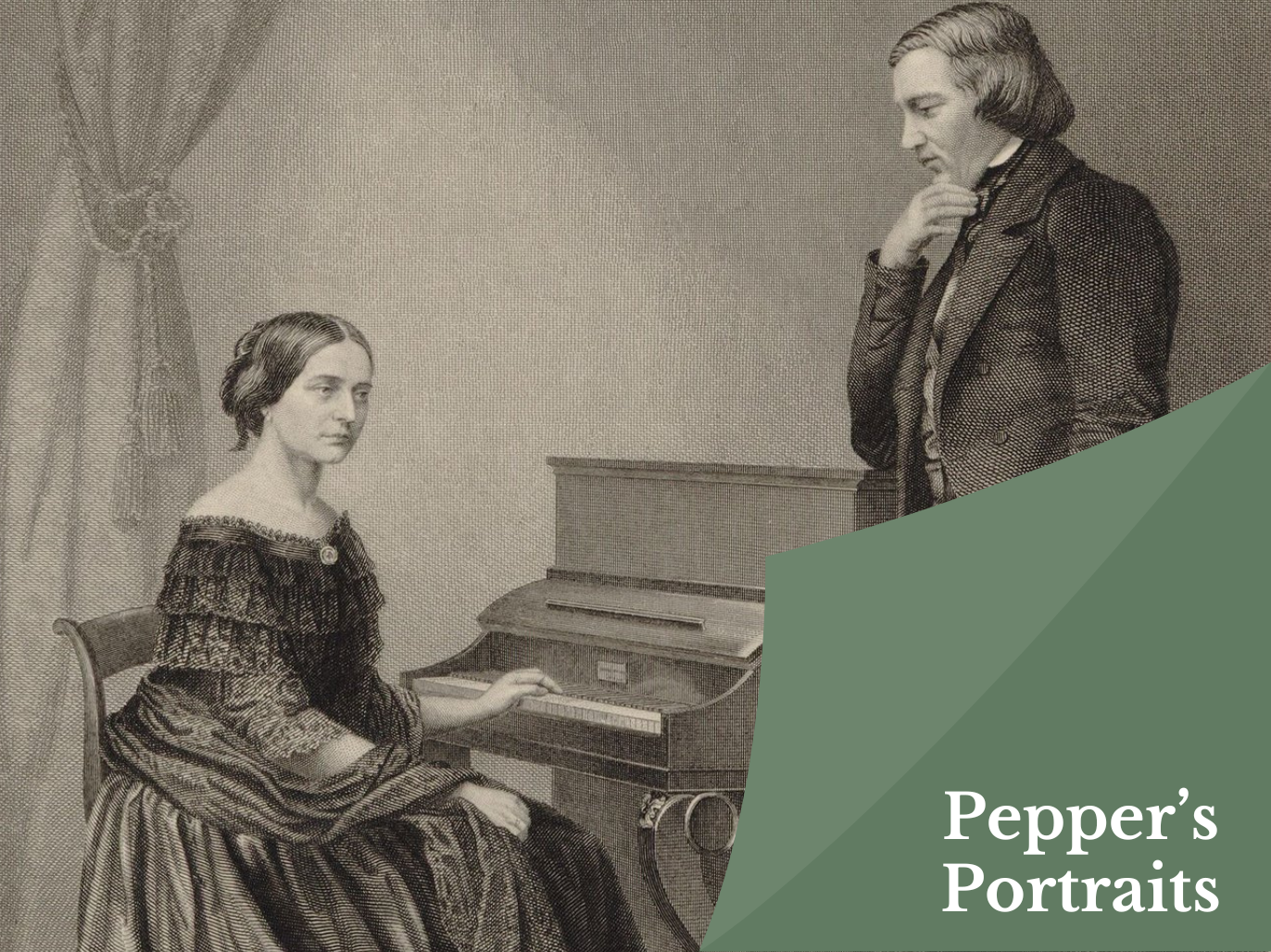

The dialogue went both ways. Clara set the words of a Friedrich Rückert poem “If You Love For Beauty” as a birthday present in their first year of marriage. Her Three Romances for violin and piano include a quotation of Robert’s Violin Sonata No. 1. Her boldest solo piano piece is her Variations on a Theme of Robert Schumann, taking his Bunte Blätter (which were in turn taken from his own earlier unpublished sketches dating back to his early twenties). Triplets, chromaticism and delicate inner voices soon enrich his noble hymn-like melody and hint at the star pianist in Clara. If any musical form can demonstrate the power of a muse, of coming together, and a conversation between partners, it’s a theme and variations.

Perhaps the most literal musical iteration of their relationship, though, is Widmung. Meaning “Dedication,” it was originally Robert’s song setting of a poem by Friedrich Rückert and given to Clara as a wedding present. The words describe the excitement of being in love. That was in 1840, the year of their marriage. Roll forward to 1872, decades after his death, and Clara made a piano transcription: a touching remembrance breathing new life into where it had all begun. Sample Lauma Skride peforming it in Leipzig in 2019 (below); the aching appoggiaturas, chromatic inner voices and sudden Schubertian harmonic shifts all create a sense of longing, heartache and profound feeling. Truly it is an emotion compressed into sound.