Some pieces of music make such a profound first impression that everything about that initial encounter is seared onto the memory. One such work, for me, is Maurice Ravel’s song-cycle Shéhérazade. I was still at school, probably about 17 years old, when one of my music teachers played me Régine Crespin’s 1963 Decca recording of the work, with Ernest Ansermet conducting the Orchestre de la Suisse Romande. The sensuality of both the words (by Tristan Klingsor, the Wagnerian nom de plume of Léon Leclère) and the music was overwhelming – heady, hothouse exoticism with perhaps a hint of danger – and Crespin’s voice could have been made especially for this piece.

View author's page

Reading time estimated : 4 min

Discover Marie-Nicole Lemieux in Ravel’s Shéhérazade.

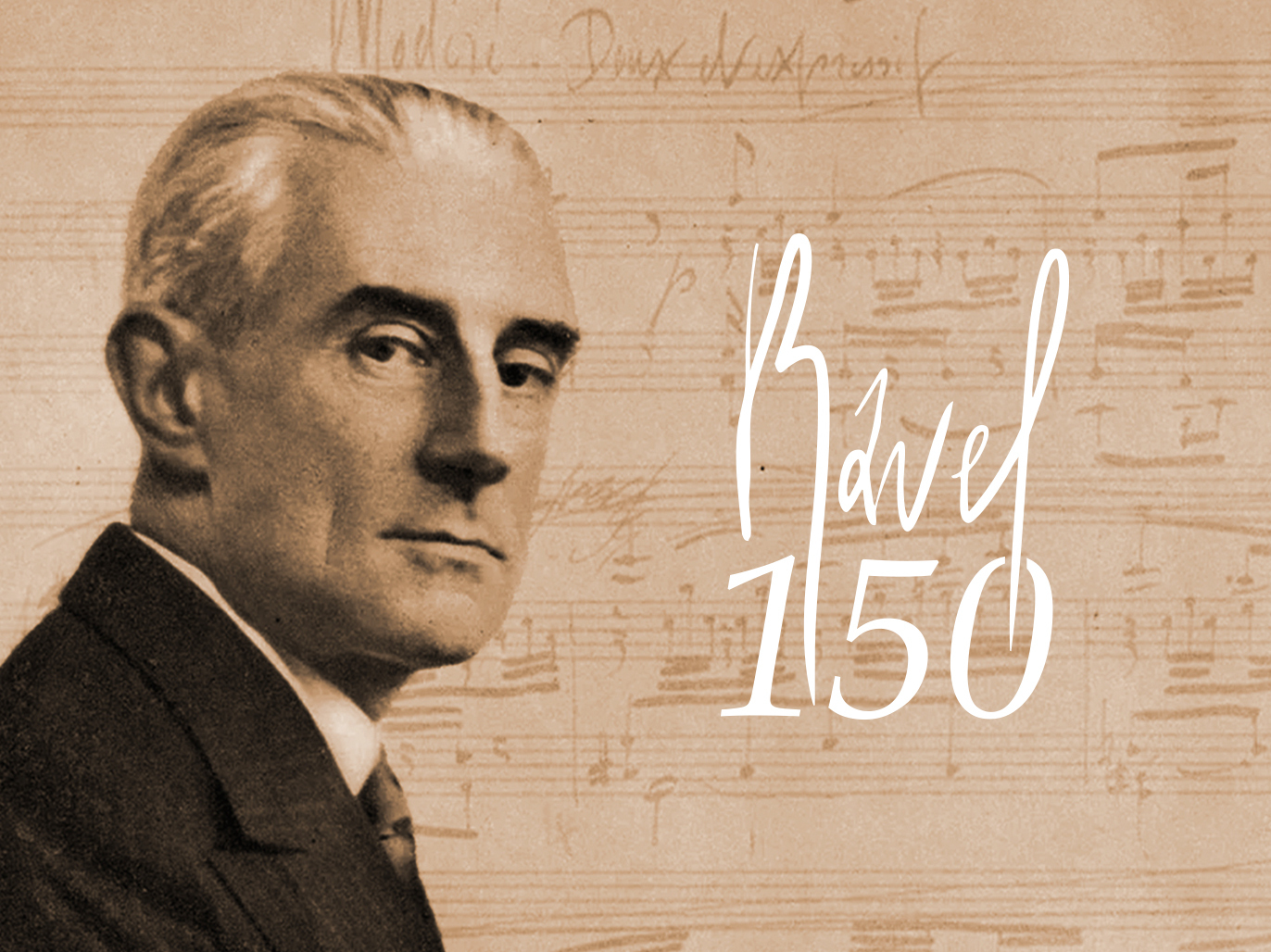

One hundred and fifty years after Ravel’s birth, we’re commemorating him, one of France’s greatest composers – and his music, pretty central to the repertoire in so many genres, is the subject of numerous concerts. One takes place at the Philharmonie de Paris and finds Bertrand Chamayou playing the complete piano works – a full evening that traces a wonderful parabola from start to close. (I sat down with Bertrand recently at the Philharmonie and talked to him about Ravel – watch it here.)

In the years since that early encounter with Shéhérazade, my love of Ravel’s music blossomed – the String Quartet, Le Tombeau de Couperin, Gaspard de la nuit, the Sonatine, the opera L’enfant et les sortilèges, Daphnis et Chloé, the piano concertos and so many more took a hold over me, one by one. It was with amazement that I later read that some people found his music cold – sure, there is a precision and clarity in much of it, but there is surely a big heart, too. Even a work like the Sonatine, written in the very first years of the 20th century, and seemingly abstract (though clearly with a nod in the direction of the 18th century), makes for me an overwhelming emotional connection; the opening movement, Modéré, with its insistent falling fourth heard right at the start, seems to crystalise a sense of loss or regret that I can’t avoid when I listen.

One element of Ravel’s genius was his complete command of orchestral colour (something that so many of his piano works seem to strain after and then achieve when the composer decided to orchestrate them). The evocation of daybreak in Daphnis et Chloé is one of classical music’s most overwhelming creations, a sonic spectacle that must surely stand on a level with the opening of both Schoenberg’s Gurrelieder and Richard Strauss’s Also sprach Zarathustra (as Stanley Kubrick so memorably noted in 2001: A Space Odyssey) as natural phenomena incomparably portrayed in music. But it is music by another composer, the Russian Modest Mussorgsky, that provided Ravel with his greatest challenge, and which resulted in one of the pieces for which he remains best known, the masterly Pictures at an Exhibition. Ravel’s orchestration of this piano suite quickly became one of the symphonic repertoire’s most popular works, and in the 103 years since its first performance in Paris, has stayed very close to music lover’s hearts. I’m sure there will be numerous encounters this year.

Celebrate the legacy of a true original with new releases, specially produced features, and deep dives into his music with medici.tv. Discover Ravel at 150 here.