When you step on stage for a concert or a recital, what do you usually think about?

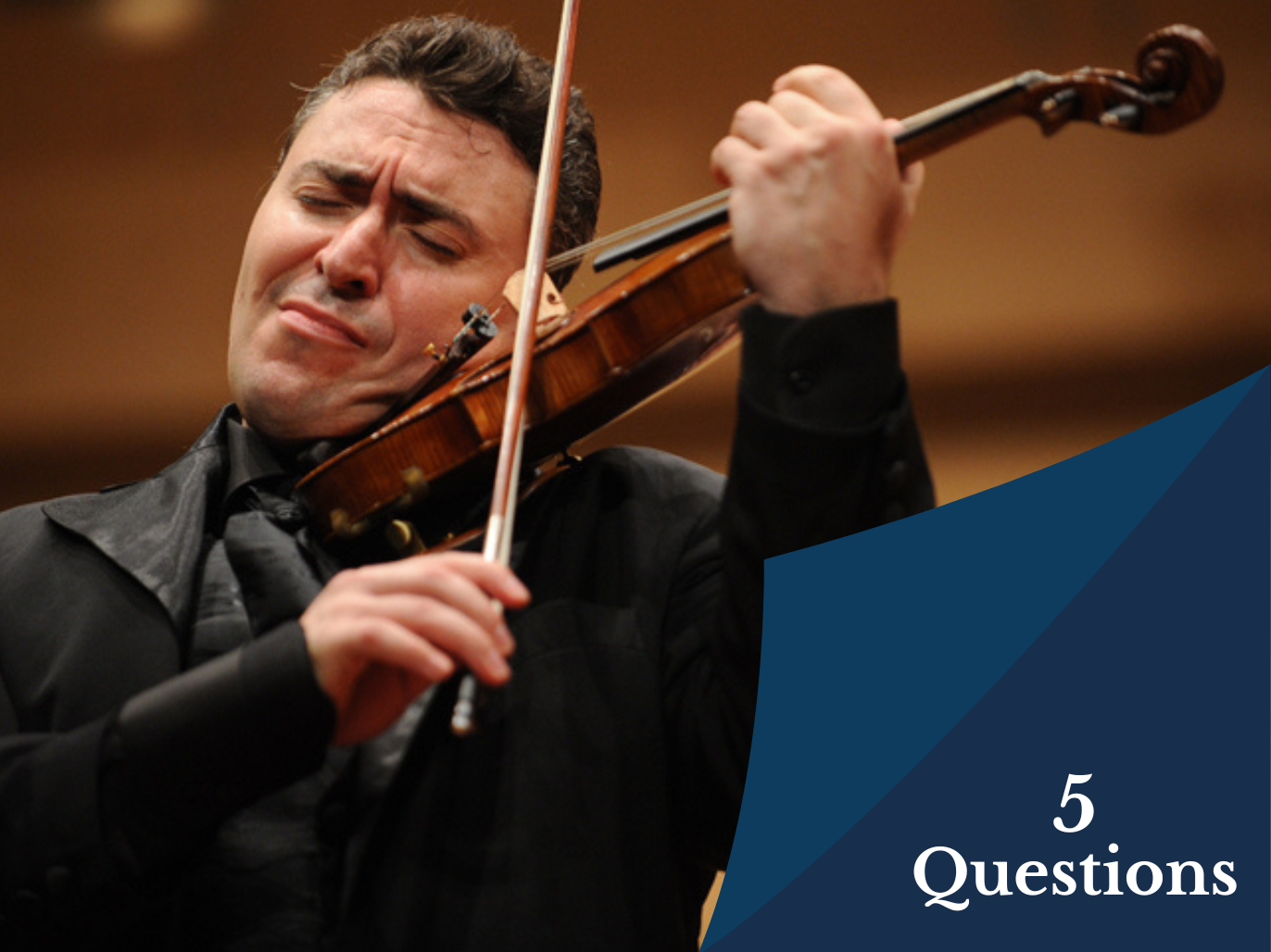

You know, for every musician — and I can only speak for myself — going on stage means connecting with the audience, the orchestra, the conductor, and bringing the music to life.

It’s a little bit like launching a rocket into the cosmos. The first five or ten minutes are crucial. Once you’ve established a connection with your body and your instrument — once you are in harmony with yourself — then you can communicate the music to the audience.

Whether you’re playing with an orchestra, a conductor, a pianist in a recital, or a chamber group, the most important thing is the connection. After you’ve established that, the concert feels like home.

And as I grow older, I feel more and more connected — to audiences, to music. I think it’s the greatest joy to be a musician.